Before the Word: A Meditation on Silence and the Poet's Notebook:

An essay on the time before the poem is written—the process of observing, listening, and recording fragmented thoughts that eventually become verses.

Before the Word: A Meditation on Silence and the Poet's Notebook

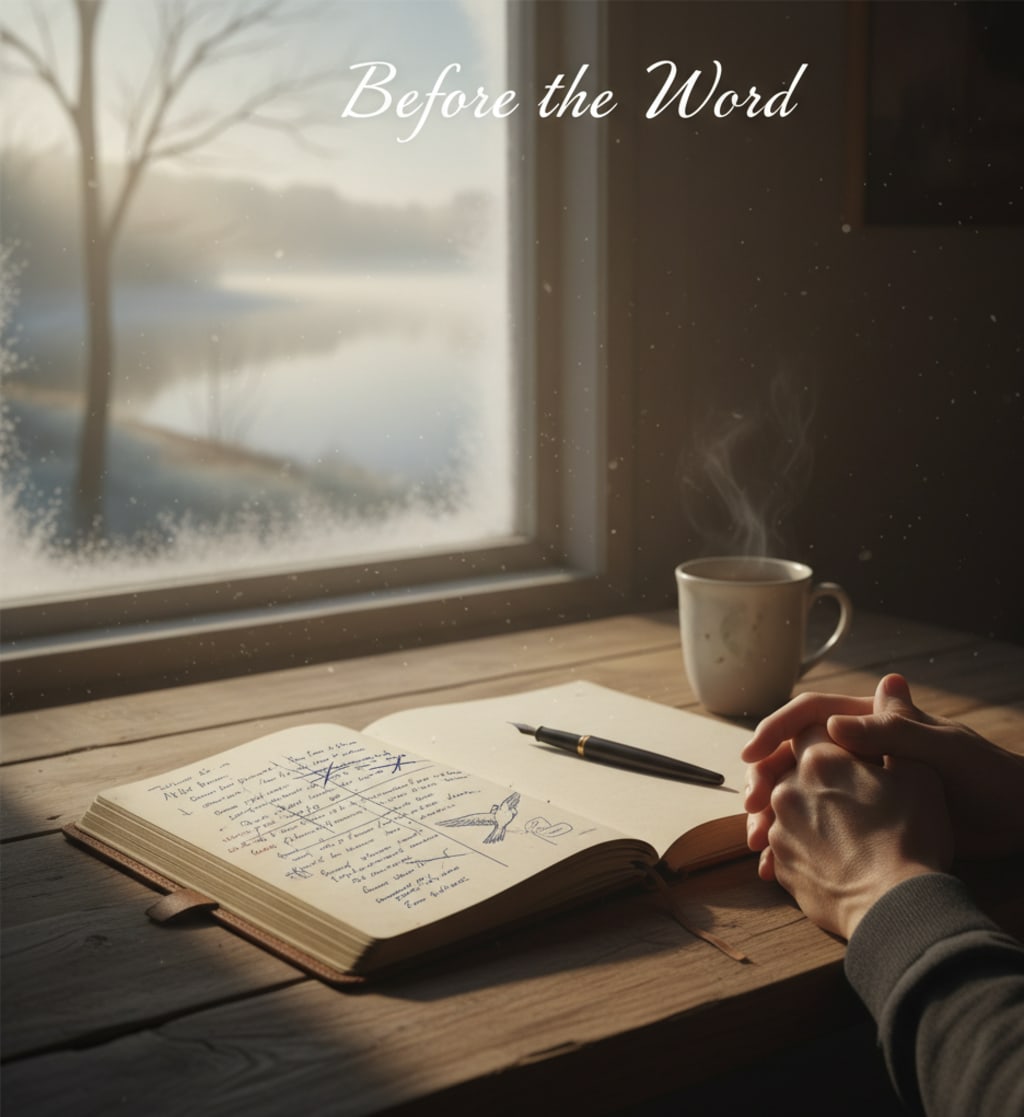

The poet’s final product, the polished poem resting neatly on the page, is an object of structure, rhythm, and deliberate articulation. It presents an ending, a resolution, or at least a temporary stillness of thought. But the most vital, chaotic, and often-overlooked stage of composition occurs long before the first draft, in a strange, liminal space—the quiet, fertile dark known as “before the word.” This phase is not about writing; it is about receiving. It is a sustained meditation built on radical silence, acute observation, and the humble, immediate act of recording fragmented thoughts.

To enter this space, the poet must first cultivate silence, not just as an absence of noise, but as an absence of internal static. The modern world is engineered for constant reply, but the genesis of a poem demands a period of non-response, a suspension of judgment and planning. This deep, internal quiet is where the true listening happens. It is the moment the external world—the rustling leaves, the distant siren, the casual, half-finished sentence overheard in a cafe—is allowed to enter the consciousness not as distraction, but as potential language. The poet listens not for meaning, but for resonance. A phrase might lodge itself simply because of the shape of its vowels, or a sound because of its jarring interruption. This receptive posture transforms the mind from an engine of interpretation into a wide-open acoustic chamber, prepared to catch the faint whispers of images and ideas that will later form the backbone of a verse.

This state of silence is inextricably linked to the art of radical observation. Passive seeing—the glance that registers only the familiar—must be shed for a hungry, active gaze. The poet is a scavenger of sensory detail, constantly searching for the unique fracture in the ordinary landscape. This is the discipline of noticing the specific shade of brown on a dying leaf, the way an alley light catches the condensation on a windowpane, or the precise tension in a stranger’s shoulder while they wait for a bus. The fragment itself is the core unit of this observation. It’s not the whole story of the cold, but the singular, visceral feeling of “the cold moves into my bones like a squatter.” It is the moment where the abstract feeling (cold) is instantly paired with the concrete, unexpected image (squatter). The poet understands that if the experience is truly felt, it will demand its own precise, metaphorical twin. The challenge here is twofold: to observe intensely, and to prevent the critical, analytical mind from prematurely packaging the observation into a theme or a narrative.

This is where the poet’s notebook assumes its essential role. The notebook is not a diary, nor is it a space for drafting finished stanzas. It is an archive of these fragments, a non-judgmental holding cell for linguistic shards and raw, immediate impressions. The content within is often messy, chaotic, and ungrammatical: half-sketched images, strange words pulled from dreams, lists of colors and textures, or emotional calculations that make no logical sense. The goal is speed and fidelity; the note must capture the sensation exactly as it arrives, before the inner editor can tidy it up or dismiss it as illogical. It is the record of the moment before the conscious will takes over. It may contain a single line, like, “The sun tasted like old paper today,” followed pages later by a shopping list, followed by a detailed drawing of a crack in the pavement. The power of the notebook lies in this chaotic juxtaposition, ensuring the raw material remains unpolished and available for later translation.

The actual writing of the poem is, in many ways, an act of translation—the slow, deliberate process of pulling these archived fragments out of the notebook’s chaos and forcing them into conversation with one another. The poet must then sift through the collection, looking for patterns, emotional echoes, or structural necessities. A phrase recorded during a morning walk might finally find its appropriate partner in a thought recorded three weeks later while waiting in a doctor’s office. This is where the mind begins to build the architecture of emotion, arranging the random observations of light, temperature, and sound into a scaffolding that can support the intended feeling.

Thus, the time before the word is revealed as the most demanding part of the poet's labor. The quality of the final poem depends entirely on the poet's willingness to be present, to listen, and to record without expectation. It is a practice in deep human presence, demonstrating that the real work of the poet is not the composition itself, but the meticulous, meditative assembly of the lived experience. The poem is merely the container; the silence and the notebooks are the inexhaustible source.

About the Creator

DreamFold

Built from struggle, fueled by purpose.

🛠 Growth mindset | 📚 Life learner

Reader insights

Good effort

You have potential. Keep practicing and don’t give up!

Top insight

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.