The Town That Had to Be Erased

Times Beach, Missouri — and the Cost of a Cheap Solution

The Town That Had to Be Erased

Times Beach, Missouri — and the Cost of a Cheap Solution

If you drive along Interstate 44 southwest of St. Louis and take the exit toward Eureka, you’ll find yourself near a quiet stretch of land hugging the Meramec River. There are trails now. Trees. Picnic tables. Cyclists moving along paved paths. Families unloading kayaks.

It feels peaceful.

But beneath that calm is one of the most disturbing environmental stories in American history — a story about a town that no longer exists.

Not because it burned down.

Not because it dried up.

Not because people simply moved away.

But because the federal government determined it was too contaminated to survive.

That town was Times Beach, Missouri.

And for nearly 60 years, it was home.

A River Town Built on Hope

Times Beach was founded in 1925 during a moment of optimism. The St. Louis Star-Times newspaper promoted small riverfront lots for sale along the Meramec River. For about $67.50 and a newspaper subscription, families could buy a piece of land.

It wasn’t glamorous. It wasn’t wealthy. But it was attainable.

People built cabins first. Then modest homes. Over the decades, it shifted from a seasonal getaway into a working-class community. By the 1970s, around 2,000 people lived there full time.

The town sat along historic Route 66. There were bars, small businesses, churches, and neighbors who knew each other’s names. It flooded occasionally — river towns do — but it endured.

No one imagined it would someday be declared uninhabitable.

The Dust Problem

The issue that would ultimately destroy Times Beach started with something ordinary: dust.

Many of the town’s roads were unpaved. During dry Missouri summers, vehicles kicked up clouds of dirt that settled on porches, laundry lines, and window screens.

Dust control was common practice in rural communities. One inexpensive method involved spraying used oil on dirt roads to keep particles from lifting into the air.

It wasn’t unusual. It wasn’t suspicious.

Town officials hired a local waste oil hauler named Russell Bliss to spray the roads in the early 1970s. He charged low rates. He had access to oil. The arrangement seemed practical.

But some of that oil wasn’t just used motor oil.

It contained industrial chemical waste.

And inside that waste was dioxin — specifically 2,3,7,8-TCDD — one of the most toxic synthetic compounds ever studied.

The Chemical Trail

The contamination traced back to a company called Northeastern Pharmaceutical and Chemical Company, often referred to as NEPACCO.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, NEPACCO manufactured chemicals including hexachlorophene, an antibacterial agent. The manufacturing process produced hazardous byproducts containing dioxin.

At the time, hazardous waste regulations were far less developed than they are today. Disposal practices varied widely, and oversight was inconsistent.

Some of NEPACCO’s waste was contracted out for disposal.

That waste eventually made its way into the hands of Russell Bliss.

Bliss mixed chemical waste with used oil and sprayed it on:

Dirt roads in Times Beach

Horse arenas

Other rural properties in Missouri

The people who hired him believed they were solving a dust problem.

Instead, they were unknowingly distributing a persistent toxic compound into the soil of their own town.

The First Warning Signs

The earliest alarm did not come from Times Beach.

It came from horses.

In the early 1970s, horses at the Shenandoah Stables in Verona, Missouri — another site where Bliss had sprayed oil — began developing severe symptoms. They suffered from lesions, weight loss, and unusual illnesses. Dozens died.

Birds fell from rafters. Small animals perished.

Veterinarians and investigators began testing soil samples. The results showed alarming levels of dioxin contamination.

This discovery led officials to examine other sites where the same oil had been sprayed.

Times Beach was on that list.

Testing the Soil

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, environmental agencies conducted soil tests throughout Times Beach.

The results revealed elevated levels of dioxin in multiple locations.

Dioxin is not something that breaks down quickly. It binds tightly to soil. It can persist for decades. High exposure levels are linked to serious health risks, including cancer and immune system damage.

For residents, the contamination was invisible. There was no smell. No color. No dramatic plume in the sky.

Just numbers on lab reports.

And those numbers were concerning.

The Flood That Changed Everything

In December 1982, the Meramec River flooded again.

Flooding was not unusual for Times Beach. But this time, it carried a new risk.

Floodwaters spread contaminated soil more widely across the town.

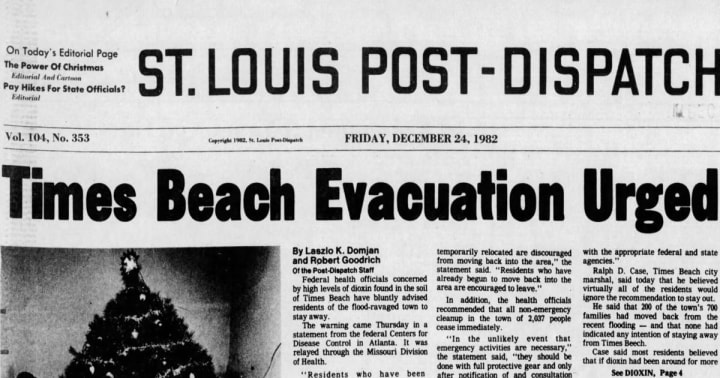

Shortly after Christmas, federal health authorities advised that residents should evacuate until further assessments could be made.

Imagine the timing. The holidays. Families gathered. Decorations still up.

And then the announcement: Your town is contaminated.

At first, some residents stayed. Others left temporarily. The uncertainty was overwhelming.

Then came the decision that sealed Times Beach’s fate.

The Buyout

In early 1983, the federal government approved a $33 million buyout of the entire town.

Approximately 800 properties were purchased. Around 2,000 residents were relocated.

It was one of the first times in U.S. history that the government agreed to purchase and dismantle an entire municipality due to environmental contamination.

Homes were appraised and bought. Residents moved to nearby towns, to St. Louis County suburbs, to wherever they could rebuild.

In 1985, Times Beach was officially disincorporated. Legally, it ceased to exist as a city.

Over time, buildings were demolished. Structures were removed. Streets disappeared.

What had been a living community became a controlled site for environmental cleanup.

Cleanup and Incineration

The remediation process lasted years.

In the 1990s, a thermal treatment facility was built to incinerate contaminated soil and debris from Times Beach and other Missouri sites affected by dioxin.

Thousands of tons of soil were treated.

By 2001, the Environmental Protection Agency removed the site from its National Priorities List, indicating that remediation goals had been achieved.

Today, the land is home to Route 66 State Park.

Visitors hike trails and picnic in areas that were once residential neighborhoods.

One of the few surviving structures, the Bridgehead Inn, now serves as a visitor center.

There are plaques explaining what happened.

But unless you know the history, you would never guess that an entire town once stood there.

Accountability

Legal proceedings followed the discovery of contamination.

Executives associated with NEPACCO were prosecuted under federal environmental laws. Two were convicted and received prison sentences and fines. Another defendant fled and later died before serving time.

Russell Bliss faced civil lawsuits but was never criminally convicted. Questions of knowledge and intent complicated prosecution efforts.

For many former residents, the legal outcomes did not fully match the magnitude of the loss.

The town was gone.

No prison sentence could rebuild it.

The Human Cost

Statistics explain contamination.

They do not explain displacement.

Families lost homes they had built with their own hands. Children left schools mid-year. Neighbors scattered.

Even when compensated financially, relocation disrupts lives in ways money cannot fix. Community is not transferable.

Former residents have held reunions over the years. They share photographs of streets that no longer exist.

They remember summers by the river. Snow days. Front porch conversations.

Times Beach was not a cautionary tale when they lived there.

It was just home.

Why This Story Still Matters

Times Beach became a defining case in environmental policy discussions. It underscored the consequences of inadequate hazardous waste oversight.

It demonstrated how contamination can transform from an industrial disposal issue into a public health crisis.

And it raised enduring questions:

Who is responsible when disposal shortcuts create generational harm?

What is the true cost of “cheap” solutions?

How do you measure the value of a town?

For Missouri residents today, it’s also a reminder that history isn’t always far away. Sometimes it’s just off the highway, disguised as a park.

The Quiet Aftermath

If you stand along the Meramec River now, it feels ordinary.

Wind through trees. Gravel underfoot.

But beneath that soil is a story about regulation, negligence, displacement, and resilience.

Times Beach does not appear on modern maps as a functioning city.

Yet it exists in memory.

And in environmental law textbooks.

And in the lives of the people who had to pack up after Christmas in 1982 and leave.

The People Who Remember

For former residents, Times Beach is not an environmental case study. It is not a policy example. It is not a footnote in regulatory reform.

It is a childhood.

It is a mortgage paid off slowly over decades.

It is a Christmas tree left standing in a living room they would never sit in again.

In interviews conducted over the years — in newspaper archives, oral history projects, and reunion gatherings — former residents often return to the same feeling: disbelief.

Many have described the moment they first heard the word dioxin as surreal. It wasn’t a word anyone used in everyday life. It didn’t feel real. There was no visible cloud. No sirens. No fire.

One former resident told reporters years later that the hardest part was not the move itself — it was the waiting. Months of uncertainty. Rumors spreading through grocery store aisles. Soil testing crews showing up with equipment. The sense that something invisible was deciding the fate of their town.

Another resident recalled being told the buyout was voluntary at first. But voluntary is complicated when the land you own is considered contaminated. When banks hesitate. When property values collapse. When the future of the town itself is unclear.

Some residents accepted the buyout quickly, seeing it as the safest option. Others resisted. They had raised children there. They had invested sweat equity into their homes. A government appraisal could not calculate that.

A woman who grew up there once described returning years later and not recognizing where her house had stood. The streets were gone. Landmarks erased. “It was like trying to remember a dream,” she said. “You know it was real, but there’s nothing left to prove it.”

There are former residents who maintain that they did not experience severe health problems. Others quietly question illnesses that surfaced years later — cancers, immune disorders, unexplained conditions. It is difficult to separate fear from evidence, correlation from causation.

But what nearly all agree on is this: losing a town is not like moving neighborhoods.

It is dispersal.

It is cultural amputation.

The community did not relocate together. It scattered.

Reunions have been held over the years — potluck-style gatherings where photographs are passed around and stories retold. People compare notes on where they were when the announcement came. Some still remember the exact day federal officials advised evacuation.

One former resident reportedly said that what hurt most was hearing outsiders refer to Times Beach as “that toxic town.” To them, it had been Little League fields and backyard barbecues.

The contamination may have defined it in headlines.

But it did not define their memories.

What Dioxin Actually Is

To understand why the government chose full evacuation over containment, it helps to understand the chemical at the center of it all.

Dioxin is not a single chemical but a group of chemically related compounds. The specific compound found in Times Beach — 2,3,7,8-TCDD — is considered one of the most toxic of the group.

It is not something manufactured intentionally as a commercial product. It is typically formed as an unwanted byproduct during certain industrial processes, including the production of herbicides and disinfectants.

Dioxin binds tightly to soil and organic matter. It does not dissolve easily in water. It does not degrade quickly under normal environmental conditions. That persistence is part of what makes it so concerning.

In humans and animals, dioxin accumulates in fatty tissue. It does not leave the body quickly. Exposure at high levels has been associated in scientific literature with:

Increased cancer risk

Immune system suppression

Reproductive and developmental problems

Skin disorders such as chloracne

Hormonal disruption

Much of what researchers know about dioxin toxicity comes from industrial accidents and from exposure linked to herbicide manufacturing, including compounds related to Agent Orange.

One of the most troubling characteristics of TCDD is that it operates at very low concentrations. Toxic effects have been observed at parts-per-trillion levels. That means even minute quantities can raise concern.

In Times Beach, soil samples in certain areas showed levels that exceeded what regulators considered safe for residential exposure.

The problem was not immediate acute poisoning. Residents were not collapsing in the streets.

The problem was chronic exposure — the possibility that children playing in contaminated soil, adults gardening, or dust entering homes could create long-term health consequences over years.

Because dioxin binds to soil, removing it is not simple. You cannot wash it away. You cannot wait for it to evaporate.

The options are limited:

Remove and incinerate the contaminated soil.

Or eliminate prolonged human exposure.

In the early 1980s, risk assessment models were still developing. Public confidence in hazardous waste oversight was already strained nationwide. Faced with widespread contamination across residential properties, federal officials made a decision that was both drastic and definitive: buy the town.

The Invisible Threat

One of the most psychologically destabilizing aspects of the Times Beach disaster was that the danger could not be seen.

Environmental disasters often conjure images of oil slicks, smoke plumes, burning rivers.

Times Beach looked normal.

Children rode bikes. Lawns were mowed. The river flowed as it always had.

Contamination lived in dust particles and soil chemistry.

That invisibility created tension. Some residents questioned whether the threat was overstated. Others feared it was understated.

Government agencies faced a dilemma: how to communicate risk without causing panic, and how to justify relocation without appearing alarmist.

The decision to buy out the entire town reflected not only contamination data but uncertainty. Long-term exposure science was still evolving. Regulators chose caution.

For the families living there, caution translated into leaving.

The Lingering Questions

Even after cleanup, even after the site became a state park, even after federal removal from the Superfund list, Times Beach remains a symbol.

It represents a moment when industrial waste disposal practices collided with ordinary residential life.

It raises questions that persist today:

How much contamination is too much?

Who bears responsibility when waste leaves its origin and enters a community?

How should risk be weighed when science is still unfolding?

For former residents, those questions are not abstract.

They are personal.

Because the town may be gone from the map.

But it is not gone from memory.

About the Creator

Dakota Denise

Every story I publish is real lived, witnessed, survived. True or not I never say which. Think you can spot fact from fiction? Everything’s true.. I write humor, confessions, essays, and lived experiences

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.