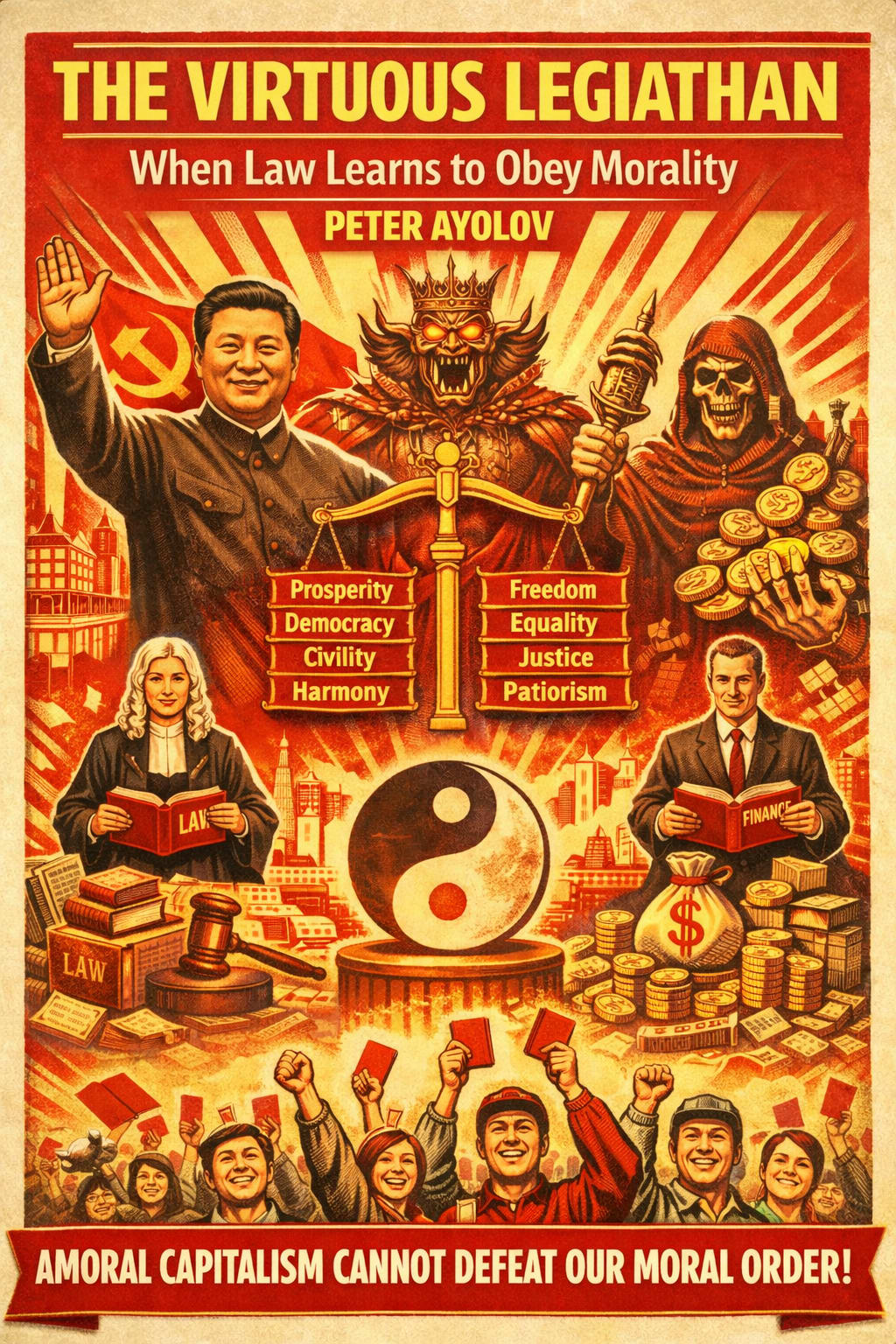

The Virtuous Legiathan

When Law Learns to Obey Morality

The Virtuous Legiathan, When Law Learns to Obey Morality

Peter Ayolov, Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski", 2026

Abstract

This article develops the concept of the Virtuous Legiathan to analyse a contemporary transformation in the relationship between law, morality, and sovereign power. Building on Peter Ayolov’s theory of Legiathan as a form of abstract, system-level domination, the article examines how moral discourse is mobilised not to restrain power, but to legitimise its concentration. Focusing on the Xi Jinping era in China, it argues that the integration of Socialist Core Values into legal, judicial, and financial governance represents a shift from rule of law as constraint to rule of law as moral instrument. Drawing on Hobbes’s theory of the Leviathan and scholarship on Confucian–Legalist statecraft, the article shows how moralisation resolves a classical problem of sovereignty: why subjects should submit their judgement to a central authority. By presenting the ruling Party as the embodiment of virtue and the ‘highest common denominator’ of social values, law is reconfigured as an apparatus that enforces ethical unity rather than pluralistic adjudication. The article concludes that this model constitutes a virtuous Legiathan: a sovereign order in which legality obeys morality, morality legitimises power, and finance, law, and governance are subordinated to a single moral–political will. This configuration challenges liberal assumptions about the separation of law and ethics and raises broader questions about sovereignty, moral authority, and the future architecture of political order.

Keywords

Virtuous Legiathan; sovereignty; law and morality; Socialist Core Values; Leviathan; pan-moralism; China; Party leadership; rule of law; moral governance

Introduction: Moral Power in the Age of Antinomianism

This article examines the conceptual alignment between Peter Ayolov’s Legiathan: The Abstract Theory of Power and the doctrine of the “Virtuous Leviathan” articulated in contemporary Chinese political theory, most visibly in the recent financial governance discourse of Xi Jinping. While emerging from radically different ideological and civilisational contexts, both frameworks converge on a shared diagnosis of late-modern power: namely, that the erosion of law, normativity, and moral restraint does not dissolve domination but reorganises it in more opaque and unaccountable forms. In Legiathan, Ayolov develops a critique of what he terms the “new antinomianism” of the twenty-first century. Drawing on the theological meaning of antinomianism as rebellion against law, he reframes the concept to describe a secular condition in which legal, social, biological, and symbolic structures are increasingly treated as arbitrary constraints to be dismantled rather than as constitutive foundations of social order. Against the Hobbesian image of the Leviathan as a sovereign guarantor of peace, Ayolov argues that contemporary power increasingly governs through managed disorder. Digital infrastructures, algorithmic markets, and performative dissent do not suppress chaos but cultivate it, transforming instability into a technique of control. Central to this argument is the paradox of the “sovereign individual”. The pursuit of absolute autonomy from norms, categories, and shared meanings renders individuals more exposed, not less, to impersonal systems of governance. In the absence of a binding nomos, power no longer appears as law or command but as environment, feed, and behavioural architecture. Ayolov’s “Legiathan” thus names a new configuration of domination: a legislated but lawless Leviathan that thrives precisely on fluidity, fragmentation, and the rejection of stable moral or legal boundaries. This theoretical framework provides an unexpected point of comparison with recent Chinese critiques of Western financial capitalism. In a series of speeches and policy interventions, Xi Jinping has advanced a vision that may be described as a “Virtuous Leviathan”: a form of neolegalism in which strict institutional control is inseparable from an explicitly moral conception of governance. His rejection of what he characterises as nihilistic or “rootless” finance mirrors Ayolov’s warning against systems that detach power from shared reality and real economic foundations. The metaphor of “water without a source” encapsulates a common concern: when finance, technology, or identity circulates without anchoring norms, it becomes self-referential, predatory, and socially corrosive. Where Ayolov diagnoses the consequences of antinomianism in Western digital societies, Xi’s intervention can be read as a strategic counter-move: an attempt to reassert law, discipline, and virtue as limits on systemic drift and oligarchic capture. The insistence on honesty, righteous gain, prudence, real-economy orientation, and strict compliance functions as a reconstructed nomos designed to prevent precisely the form of algorithmic and financial Legiathan that Ayolov describes. In this sense, the “socialist Wall Street” project is not merely an economic programme but an effort to bind power back to moral purpose. By placing Legiathan in dialogue with the theory of the Virtuous Leviathan, this article argues that the central political conflict of the present is not simply between liberalism and authoritarianism, but between antinomian systems that dissolve law into managed chaos and neolegal systems that seek to re-anchor power in enforceable norms and internalised virtue. Whether such anchoring can avoid its own pathologies remains an open question, but the comparison clarifies a shared intuition on both sides: that lawlessness, not law, has become the preferred medium of domination in the digital age.

Finance as Moral Infrastructure

In his January 2024 address to the Central Financial Work Conference, Xi Jinping places money and finance at the very core of political sovereignty and moral order. Far from treating finance as a neutral technical subsystem, the speech frames it as a decisive instrument through which a community either preserves its autonomy or dissolves into dependency, instability, and moral decay. Monetary systems, in this view, are not merely economic infrastructures but expressions of collective purpose and ethical limits. Xi’s intervention is directed against what he explicitly characterises as financial nihilism: a condition in which capital circulation becomes an end in itself, detached from production, social responsibility, and political accountability. When finance ceases to serve the real economy, it no longer mediates value but merely redistributes power. In such a system, wealth is generated not through creation but through abstraction, leverage, and self-referential speculation. The result is not prosperity but systemic fragility and political vulnerability. The metaphor repeatedly invoked in the speech—“water without a source, a tree without roots”—captures this logic with striking precision. Finance separated from material production and moral restraint is structurally self-destructive. It consumes the very foundations on which it depends, hollowing out the productive base of society while concentrating power in increasingly ungovernable elites. Sovereignty erodes not through foreign invasion but through internal financialisation, as states lose control over the mechanisms that allocate credit, risk, and long-term investment. From this perspective, Xi’s call for a “modern financial system with Chinese characteristics” is best understood as an attempt to restore the political primacy of money. Finance is redefined as a servant of national development, social stability, and shared prosperity rather than as an autonomous sphere governed by market logic alone. Reserve currency status, often highlighted in Western commentary, appears here as a secondary consequence rather than a strategic goal. Trust in a currency emerges from the moral and institutional credibility of the system that issues it, not from speculative dominance or financial innovation for its own sake. Central to this argument is the claim that institutional regulation alone is insufficient. Legal frameworks without moral culture produce actors skilled at exploiting loopholes rather than serving the common good. This insight situates Xi’s speech within a long-standing Chinese political debate between Legalist enforcement and Confucian moral cultivation. Sustainable order, the speech implies, requires both external constraint and internalised norms—what Confucian tradition describes as chǐ, a sense of shame or moral self-regulation that operates even in the absence of surveillance. The five ethical principles outlined in the speech—honesty, righteous gain, prudence, commitment to the real economy, and strict compliance—function as a moral architecture designed to prevent the capture of the state by financial oligarchies. They are explicitly framed as safeguards against the corruption of public policy, regulatory capture, and the emergence of unaccountable elites. Notably, Xi acknowledges that China itself has exhibited early symptoms of these pathologies, particularly where party discipline weakened and financial actors pursued self-interest over collective goals. What is at stake, therefore, is not simply economic efficiency but the moral coherence of the political community. A financial system organised around unchecked profit maximisation undermines solidarity, corrodes trust, and ultimately destabilises governance. Conversely, a system that subordinates finance to social purpose seeks to preserve sovereignty by aligning economic power with collective values. Seen in this light, Xi’s intervention resonates strongly with contemporary critiques of digital and financial abstraction. It poses a question that has largely disappeared from Western political discourse: what is finance for? By restoring this question to the centre of governance, the speech reframes money not as a neutral medium but as a moral and political institution. The emerging global divide, then, is not merely between currencies or markets, but between systems that treat finance as an autonomous force and those that insist it remain accountable to the ethical foundations of the community it claims to serve.

Virtuous Leviathan or Digital Legiathan?

In Peter Ayolov’s theoretical framework, the contemporary Chinese vision of a “socialist Wall Street” articulated by Xi Jinping can be read as a concrete political response to the condition diagnosed in Legiathan: The Abstract Theory of Power. Where Legiathan describes the rise of a lawless yet fully legislated form of domination produced by digital antinomianism, Xi’s January 2024 intervention outlines what may be called a project of virtuous neolegalism: a deliberate attempt to rebind power, finance, and governance to moral and legal constraints in order to prevent systemic decay. Ayolov’s core claim is that Western late-modern societies have entered an antinomian phase in which law, normativity, and structure are increasingly treated as oppressive fictions rather than as foundations of collective life. In this environment, rebellion against rules does not weaken power but reshapes it. Authority migrates from visible institutions to invisible architectures: algorithms, markets, and performative dissent. Finance, detached from the real economy and shielded by ideological narratives of freedom and innovation, becomes one of the most advanced expressions of this transformation. Oligarchic capture of public policy appears not as a breakdown of the system but as its logical outcome. Xi’s speech directly addresses this same pathology from a radically different ideological position. Rejecting what he characterises as Western financial nihilism, he argues that finance severed from moral purpose and real economic foundations becomes self-referential and destructive. His now widely cited metaphor of “water without a source, a tree without roots” names precisely the condition Ayolov describes as the emergence of a digital-feudal Legiathan: a system that feeds on circulation itself, producing volatility, inequality, and political instability rather than social order. At the centre of Xi’s argument is a rejection of the assumption—dominant in Western political economy—that institutional design alone can discipline self-interest. Against this legalist minimalism, he advances a synthesis of rule of law and rule of virtue. Enforcement without internalised norms, he suggests, produces actors skilled only in exploiting loopholes. Sustainable order requires not only regulation but moral culture: a shared understanding of limits, responsibility, and purpose. This return to a Legalist–Confucian logic mirrors Ayolov’s insistence that the collapse of the nomos does not liberate individuals but exposes them to more total forms of control. Both frameworks also converge on the problem of oligarchic hijacking. Ayolov describes a paradigm in which power is obscured by constant symbolic rebellion, while real decision-making concentrates in financial and technological elites. Xi’s speech acknowledges analogous dangers within China itself, admitting that loosened party discipline and the prioritisation of self-interest had already begun to erode institutional integrity. The response, in his formulation, is not deregulation but intensified moralisation of power: a reaffirmation that no financial actor stands above collective authority. The five principles outlined in Xi’s January 2024 study session—honesty, righteous gain, prudence, real-economy orientation, and strict compliance—function as a reconstructed nomos designed to prevent the very chaos Ayolov warns against. By framing finance as a servant rather than a sovereign, Xi attempts to restore an anchoring function that Ayolov argues Western societies have largely surrendered to algorithmic mediation and market abstraction. This first part of the article situates the Chinese project of a “Virtuous Leviathan” not as an ideological curiosity, but as a systemic counter-proposal to the antinomian condition analysed in Legiathan. Whether such a project can succeed without reproducing new forms of domination remains an open question. What is already clear, however, is that the central conflict of contemporary power is increasingly framed as a choice between managed lawlessness and enforced moral order—between submission to the feed and submission to a renewed nomos.

Moralised Law, Party Sovereignty, and the Ethics of Order

In ‘Creating a Virtuous Leviathan: The Party, Law, and Socialist Core Values’(2019) Delia Lin and Susan Trevaskes argue that the Xi Jinping administration has moved decisively towards a model of governance in which Party leadership is asserted as the organising principle of the entire legal system, while moral doctrine is simultaneously written into the language, procedures, and aims of law itself. Their analysis is useful here because it names, with unusual conceptual clarity, the mechanism by which a state attempts to convert finance, legality, and public ethics into a single sovereign architecture: not merely by tightening regulation, but by moralising regulation. The Party’s insistence that its leadership be implemented ‘across the complete process’ of governing according to law is paired with a propaganda and policy programme that integrates ‘Socialist Core Values’ into legislation, adjudication, and judicial reasoning. In this arrangement, law does not operate as an independent constraint on power, but as a vehicle for a prescribed moral horizon, presented as the ‘highest common denominator’ of the people’s values and therefore as the ethical warrant for political supremacy. Lin and Trevaskes describe this as a form of ‘pan-moralism’: an expansive claim that moral standards must govern domains normally regulated by legal rules and institutional boundaries. The resulting synthesis extends the Hobbesian image of Leviathan by adding a modern ideological core: sovereign power is legitimated not only as the guarantor of order, but as the authorised producer of moral unity, tasked with aligning the ruled and the rulers through ‘unification of thought’. This matters for the question of money and sovereignty because it clarifies the deeper rationale behind financial governance in the Xi era: finance is treated as too politically dangerous to be left to autonomous market logics, and too morally consequential to be governed by technical rules alone. A monetary system can only secure sovereignty, on this view, if it is anchored in enforceable discipline and internalised virtue at the same time, so that the community’s moral culture becomes a stabiliser of economic behaviour, and the law becomes an instrument for consolidating that culture. Lin and Trevaskes therefore provide a precise vocabulary for understanding how a state seeks to protect itself from ‘rootless’ abstraction and oligarchic capture: by constructing a ‘virtuous Leviathan’ in which the Party claims legal authority, moral authority, and the right to define the ethical purposes to which economic life, including finance, must remain subordinated. The authors note that the CCP’s 2016 ‘Guiding Opinions’ require all laws, regulations, and public policies to be used to steer ‘correct value orientations’ in society, turning moral principles into binding legal norms. They emphasise that this is the first time the Party has demanded a prescribed set of values—the Socialist Core Values—be integrated across legal and judicial processes, including routine court decision-making. They argue that the stated aim of this moral–legal fusion is a ‘unification of thought’ between the Party and the people, so that governing through law is inseparable from cultivating obedience through virtue. They also stress that by presenting Socialist Core Values as the ‘highest common denominator’ of national values, the Party gains ideological grounds to treat law as an instrument for consolidating Party supremacy rather than as an independent constraint on power.

Moral Supremacy and the Architecture of Sovereignty

In their influential analysis, Delia Lin and Susan Trevaskes argue that the Xi Jinping administration has moved beyond the integration of law and morality as a governing technique toward a more ambitious project: the moral justification of absolute Party supremacy. Their central claim is that the contemporary promotion of Socialist Core Values functions not merely as ethical guidance, but as an ideological mechanism that legitimates the concentration of sovereign power in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) itself. This shift coincides with constitutional amendments affirming that the Party leads ‘all areas of endeavour’ across society, the state, the military, and civil institutions, thereby formalising a model of governance in which political authority is indivisible and total. Lin and Trevaskes situate this transformation within a Hobbesian framework, arguing that the CCP increasingly resembles a modern incarnation of the Leviathan: a single common power established to secure order, unity, and protection in exchange for the submission of individual judgement and autonomy. Yet they emphasise that a purely Legalist or authoritarian explanation is insufficient to account for the Xi era. Unlike a system grounded solely in coercion and fear, the Party’s claim to legitimacy is increasingly framed in moral terms. Through the language of virtue, happiness, and ‘a better life’, the CCP presents itself not only as the guarantor of stability, but as the ethical embodiment of the people’s will. This moralisation of sovereignty becomes particularly visible in institutional reforms such as the creation of the National Supervision Commission, which consolidates Party and state disciplinary powers into a single apparatus overseeing all public servants. Crucially, this expansion of surveillance and control is justified not as a security measure alone, but as a project of ‘building high moral standards’. In Hobbesian terms, obedience is no longer secured merely by the promise of peace, but by the assertion that the sovereign itself incarnates the highest moral values of the community. The Party thus claims the right not only to rule, but to define virtue, justice, and correctness through law. Lin and Trevaskes argue that this move resolves a classic Hobbesian problem: why subjects should surrender their will to a sovereign whose legitimacy rests only on security. The CCP circumvents this dilemma by adopting a pan-moralist stance rooted in the Confucian–Legalist tradition, asserting that Party leadership, Socialist Core Values, and the will of the people are organically unified. By presenting itself as both the moral teacher and the political sovereign, the Party transforms submission into an ethical duty rather than a purely contractual exchange. The result is what the authors describe as a ‘virtuous Leviathan’: a sovereign entity that claims unchallengeable authority not only through law and coercion, but through moral supremacy. In this configuration, law becomes the instrument through which moral doctrine is enforced, and morality becomes the justification for the concentration of power. The CCP, as commonwealth, demands that citizens align their judgement with its own, thereby rendering pluralism, autonomous moral agency, and legal independence structurally incompatible with the political order it seeks to consolidate.

Conclusion: When Morality Becomes Sovereign

This article has argued that the emergence of the Virtuous Legiathan marks a significant transformation in the architecture of contemporary power, one in which law no longer functions primarily as a constraint on authority but as a vehicle for moral consolidation. By placing Peter Ayolov’s concept of Legiathan in dialogue with the Xi Jinping administration’s project of moralised governance, the analysis has shown that the central political tension of the present is not reducible to a simple opposition between liberalism and authoritarianism. Rather, it is a struggle between antinomian regimes that govern through managed lawlessness and neolegal regimes that seek to stabilise power by re-embedding it in enforceable norms and internalised virtue. In both cases, morality does not disappear; it is either dissolved into algorithmic abstraction or reassembled as an instrument of sovereignty. The Chinese model examined here demonstrates how moral discourse can be mobilised to resolve a classical problem of political theory: why individuals should submit their judgement to a central authority. Through the integration of Socialist Core Values into law, finance, and institutional design, the Party claims not only legal supremacy but moral authorship of the social order itself. Finance becomes a privileged site of this transformation, treated as too consequential to be governed by market logic alone and too dangerous to be left without ethical anchoring. In this configuration, sovereignty is secured not merely by coercion or efficiency, but by the assertion that collective virtue and political authority are indistinguishable. At the same time, the analysis raises an unresolved question that extends beyond the Chinese case. If antinomian systems produce domination through chaos, and virtuous neolegal systems produce domination through moral unity, then the problem confronting contemporary societies is not simply how to restore law or morality, but how to prevent either from becoming totalising. The Virtuous Legiathan exposes a paradox at the heart of modern governance: that the attempt to save society from lawlessness may culminate in a form of order in which legality obeys morality, morality legitimises power, and plural judgement becomes structurally incompatible with sovereignty. Whether such systems can stabilise political life without extinguishing moral autonomy remains an open question—one that will define the future contours of law, finance, and power in the post-liberal age.

‘The more laws and restrictions there are,

the poorer people become.

The sharper the weapons,

the greater the chaos in the state.’

(Dao De Jing, Chapter 57)

Bibliography

Ayolov, P. (2026). Legiathan: The Abstract Theory of Power. Amazon Kindle

Xi Jinping (2024). ‘Speech at the Central Financial Work Conference Study Session’, January 2024, Beijing. Published with commentary in Qiushi (求是), Chinese Communist Party theoretical journal.

Lin, D. and Trevaskes, S. (2019) ‘Creating a Virtuous Leviathan: The Party, Law, and Socialist Core Values’, Asian Journal of Law and Society, 6(1), pp. 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/als.2018.41

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.