Green and Pleasant

A landscape made from a heap of skeletons

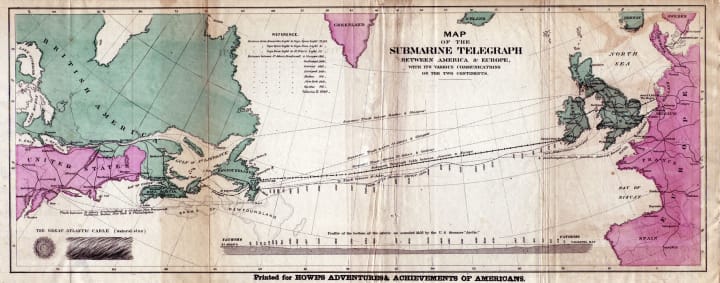

In 1857, Lieutenant Commander Joseph Dayman was dispatched by the Admiralty at the helm of HMS Cyclops to take deep sea soundings in preparation for the first transatlantic telegraph cable. The laying of this cable, which ran between Ireland and Newfoundland, was as monumental an undertaking as any of its time and, inevitably, its completion was accompanied by lavish celebrations and rambling tributes to engineering excellence.

A special committee organised a day of events in New York that brought together church services, speeches, a one hundred gun salute, firework displays, a four mile long procession of 15,000 New Yorkers and the illumination of public buildings. City Hall, indeed, became illuminated in quite the wrong way when a stray firework set fire to the roof, but even that didn’t seem to dampen the enthusiasm for celebrating human ingenuity and endeavour.

Unfortunately, the party turned out to be a little premature and the magnificent achievement an all-too brief triumph of science over adversity.

Flickering into life on the 16 August 1858, the connection lasted long enough for Queen Victoria and US President James Buchanan to exchange pleasantries in morse code but was burnt out barely a month later when Wildman Whitehouse, chief electrician to the Atlantic Telegraph Company, pumped 2000 volts down the cable in an experiment to improve data transmission speeds and inadvertently turned it into the world’s largest and most ineffectual immersion heater.

The public excitement around the first working, albeit briefly, transatlantic telegraph was followed in its rapid failure by bitter disappointment. There were allegations that the whole thing was a hoax or, at best, that it was cooked up by cynical stock market speculators out for a quick buck. With potential investors as skeptical as the public, it wasn’t until 1866 that another cable was attempted as the world’s first permanent transatlantic telegraph was laid by the SS Great Eastern and memories of the first failure had receded enough to ensure a great hullabaloo. However, in the intervening period, in the much less flamboyant world of geology, a great deal had already been made of the soundings taken by Captain Dayman aboard the Cyclops.

Dayman had forwarded specimens of mud brought up by the Cyclops to Thomas Henry Huxley, an eminent scientist of the day, who wrote of the mission with characteristic humour:

“The Admiralty consequently ordered Captain Dayman, an old friend and shipmate of mine, to ascertain the depth over the whole line of the cable, and to bring back specimens of the bottom. In former days, such a command as this might have sounded very much like one of the impossible things which the young Prince in the Fairy Tales is ordered to do before he can obtain the hand of the Princess. My friend performed the task assigned to him, without, so far as I know, having met with any reward of that kind.”

Huxley didn’t know it at the time, but he was to examine mud that would not only describe the nature of the ocean floor, but also an explanation of how chalk is formed – an explanation that, 160 years later, hints at how the environment dynamically manages itself using mechanisms of bio-feedback. These mechanisms would, in turn, prove to be at the heart of a very contemporary concern – that of climate change.

Huxley examined the samples of mud – which he referred to as ‘ooze’ – obtained by Dayman and found that, chemically, it was “composed almost wholly of carbonate of lime” and that a section of the ooze placed under a microscope revealed “innumerable Globigerinæ imbedded in a granular matrix”. Globigerina is a kind of plankton – a single celled animal that lives at or near to the surface of the sea and grows a small shell – or test – around itself.

Examining the ‘granular matrix’ in which the Globigerinæ were embedded, Huxley noted that all its constituent particles seemed to have a definite form and size.

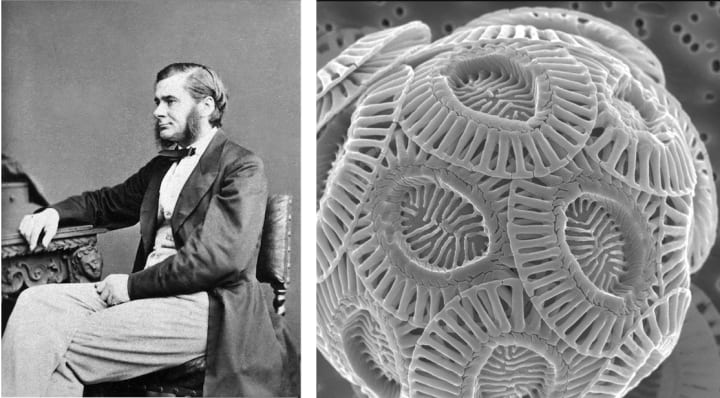

“I find in almost all these deposits a multitude of very curious rounded bodies, to all appearance consisting of several concentric layers, surrounding a minute clear centre, and looking, at first sight, somewhat like single cells of the plant Protococcus; as these bodies, however, are rapidly and completely dissolved by dilute acids, they cannot be organic, and I will, for convenience sake, simply call them coccoliths.”

A few years later, Huxley was sent the report of army surgeon Dr George Wallich, who was seconded by the Navy to serve on a similar survey, this time to take soundings and samples for another cable over an alternative route. Wallich was recommended for the position by Huxley and. although the cable was never laid, the survey nevertheless proved very useful to science.

Wallich found the coccoliths that Huxley had discovered but also noticed spheroidal accumulations of them, which he termed ‘coccospheres’. Wallich linked the coccoliths and coccospheres to those found by another great Victorian polymath, Henry Clifton Sorby, who had ground down a sliver of chalk to a thousandth of an inch and looked at it under a microscope – a revolutionary technique at the time. He hadn’t been the first to note them – that honour falling to the German scientist Christian Ehrenberg, who had referred to ‘crystalloids of chalk’ twenty years before HMS Cyclops had even set sail – but Sorby’s technique had greatly improved upon Ehrenberg’s earlier description.

Between them, these four men had proven that chalk is almost entirely made out of fossils, albeit very small ones – or, calcareous nannofossils as they are known today. To use Ehrenberg’s words, chalk is “nothing more but a heap of skeletons”.

Huxley was posthumously awarded due credit for his work with coccoliths when the most numerous species of coccolith bearing phytoplankton Emiliania huxleyi – scientists today refer to it as Ehux – was named after him. As it turns out, Ehux and its ancient ancestors are perhaps the most astonishing creatures on the earth. To find out why, we should take a moment to consider what trillions of coccoliths, along with the globigerinae, have left behind – chalk.

A green and pleasant land

By the time that Huxley had written up some of his findings in an 1868 article for Macmillan’s Magazine called “On a Piece of Chalk”, a skillful reconstruction of much of the geology of the British Isles extrapolated from a small chunk of East Anglian downland, the rolling hills of Southern England had long occupied a unique place in our patriotic awareness. Indeed, if there was a national poll then or now to find the landscape that articulated the concept of ‘England’ best, the downs of the east and south east of Britain would win – and it doesn’t take a genius to see why.

Downland is both green and pleasant, after all and, as all students of William Blake and members of the WI will be keen to inform you – perhaps, even in song – England is a green and pleasant land. The lyric to Jerusalem comes from the introduction to Blake’s epic poem Milton and it is inconceivable that the line “In England’s green and pleasant land” was not a reference to, or at least inspired by, the downlands and coast just east of Bognor Regis in Sussex where he lived.

Carried on a rousing, rolling anthem, it’s hard to stop the mind’s eye from watching a cinematic flyby over numinous low hills – a patchwork of fields dissected by cool, clear streams – but in a country blessed with such a wide variety of scenery in different shades of green and varying degrees of pleasantness, what is it about this particular landscape that marks it out as so English?

About the Creator

Ian Vince

Erstwhile non-fiction author, ghost & freelance writer for others, finally submitting work that floats my own boat, does my own thing. I'll deal with it if you can.

Top Writer in Humo(u)r.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.