Scientists were surprised to learn that Mars has been losing water.

Water loss is reshaped by minor dust storms.

Mars may be losing water in ways that scientists had not completely thought about, according to a brief dust storm that occurred there.

Large volumes of water vapour were transported into the upper atmosphere by the localised storm during what is often a calm northern summer. This season was previously believed to have a negligible impact on long-term water escape.

The finding adds a fresh element to the puzzle of how Mars gradually dried out over billions of years by indicating that even short regional weather events can cause bursts of hydrogen leakage to space.

Researchers now understand how short-term disruptions might have influenced long-term water loss by connecting a single storm to increases in high-altitude water and escaping hydrogen.

These brief occurrences might have contributed to the planet's slow transition from a wetter world to the icy desert it is today.

During the off-peak season, a dust storm

Mars is projected to keep its remaining water frozen low in its atmosphere during a typically quiet northern summer, which is when the occurrence took place.

Tohoku University researcher Shohei Aoki recorded a dramatic increase in high-altitude water that was directly linked to a brief regional dust storm, and orbital measurements recorded the shift.

This year's occurrence was unique in that it lifted significantly more vapour than was typical for the season, and shortly after, there was a noticeable rise in hydrogen escaping.

A process that was previously largely ascribed to Mars' warmer southern months now has a rare, time-limited perturbation at its core due to that little window of activity.

Summertime presumptions disproved

Scientists have long anticipated that little water would ascend high into the sky since northern summer typically cools Mars and keeps airborne dust low. Instead of lofting vapour upward, cold air causes water to freeze into clouds, trapping it into lower levels.

The same trap diminishes and dustier skies warm during the warmer southern summer, allowing more vapour to survive at higher elevations.

Researchers' estimates of long-term water loss were influenced by this cyclical pattern, which gave global dust events and southern storms the greatest attention.

Therefore, the northern summer was considered a low-risk season for water escape in current climate models. This latest incident, however, demonstrated that models failed to account for the way a concentrated dust plume may quickly warm the atmosphere and reduce the ability of clouds to form in a small area.

IAA-CSIC researchers contended that because brief, strong occurrences can occur outside of the season that scientists are most interested in, they should be given greater consideration.

Although proper accounting is currently complicated by rapid atmospheric changes, improved projections will necessitate faster simulations and orbit-to-orbit monitoring.

Water loss is reshaped by minor dust storms.

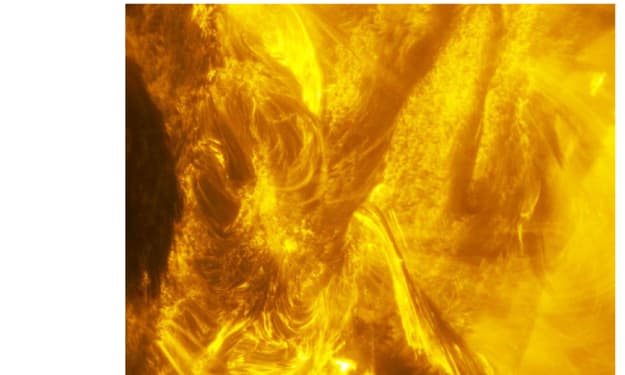

The way the regional storm operated was by filling the air with dust, which swiftly heated the intermediate atmosphere by absorbing sunlight. Because warmer air raises the temperature at which clouds develop, more water evaporates as vapour instead of condensing.

That vapour was transported upward by winds and atmospheric circulation as the storm grew, from the vicinity of the surface into thinner levels of the atmosphere.

Massive dust storms that shroud the entire planet in haze were the main topic of discussion in earlier discussions regarding Martian water loss. Instruments continued to detect a strong atmospheric response above the typical cloud layer, but this event remained regional.

The increase altered the way scientists identify significant loss occurrences, but it did not endure long enough to dominate the annual water budget.

The occurrence demonstrates that Mars can lose water outside of the season that scientists had thought to be most significant, even if the annual total stays minimal.

Hydrogen escaped due to a surge in water.

An anomalous increase in water vapour across northern high latitudes was recorded by measurements. In the northern summer, midair water levels could be up to ten times higher at altitudes over 25 miles (40 km).

Even after multiple summers of orbital surveillance, the researchers had not observed anything like this in previous Martian years. Water sits closer to space until it reaches these heights, which makes atmospheric escape simpler than previously thought.

Increased hydrogen was observed in the vicinity of the area where Mars' atmosphere merges with space in the same season, just after the storm.

High-altitude water vapour is broken up by sunlight, releasing hydrogen atoms that may float into space. According to the results, at the same seasonal peak, hydrogen levels were 2.5 times higher than in prior years.

The study's co-author, Adrian Brines, a researcher at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, said, "The findings reveal the impact of this type of storm on the planet's climate evolution and opens a new path for understanding how Mars lost much of its water over time."

illustrating how dust storms affect

Multiple spacecraft monitoring distinct levels of Mars' atmosphere provided the researchers with evidence, enabling them to cross-check every stage of the procedure.

Through the analysis of sunlight, Europe's Trace Gas Orbiter monitored the rise of water vapour into the middle atmosphere. Temperature profiles and weather maps from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter helped track the storm's development and the ensuing warming trend.

In the meantime, the Emirates Mars Mission directly connected increased water vapour to air escape by using an instrument to analyse hydrogen at higher elevations.

Mars' climate is changed by dust storms.

The new road creates an additional channel for water loss, and Mars did not dry out in a single, clear step. Even minor additional losses can mount up over billions of years, particularly if storms were more frequent on ancient Mars.

Although the storm seen in contemporary data is exceptional now, Mars has not always had the tilt, orbit, or dusty behaviour that it does now, indicating that similar occurrences may have happened more frequently in the past.

"These results demonstrate that brief but intense episodes can play a relevant role in the climate evolution of the Red Planet and add a crucial new piece to the incomplete puzzle of how Mars has been losing its water over billions of years," Aoki said.

The new results tighten the causal chain by connecting a brief storm to both high-altitude moisture and subsequent hydrogen escape.

The frequency of these northern storm occurrences and whether similar bursts contributed to water loss throughout previous periods of Martian climate history may now be tested using future orbiter measurements and updated climate models.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.