The Lost Art of Political Cinema: A Reflection on the Past and Present.

Exploring the Shift from Thought-Provoking Political Cinema to Mainstream Satire. Why True Political Storytelling Still Matters

As you may have guessed from the cover image, I recently watched Don't Look Up. I personally believe it was a well-scripted and well-directed film, featuring an impressive cast and a solid sense of humor. However, after scrolling through social media, I noticed many viewers and writers describing the movie as a groundbreaking satire—one that elevates political humor to a new level.

With all due respect to the filmmakers and the brilliant cast, the level of political humor in Don't Look Up barely surpasses that of a Last Week Tonight with John Oliver episode. My aim here is not to indulge in nostalgia, though I do appreciate specific eras of cinema. Rather, I believe there are still remarkable examples of political filmmaking today—such as Michel Franco's New Order or The Death of Stalin from a few years ago. Unfortunately, these films receive far less mainstream attention and distribution, making them harder to access. But has political cinema ever been mainstream? If you asked yourself this while reading, thank you. In this article, I explore how political films have historically influenced cinema and why they still matter today.

Coming from Greece, a country with a rich tradition of political cinema, I grew up in a culture of exceptional filmmakers such as Theo Angelopoulos and Costa-Gavras. Their work serves as a testament to the power of film as a political act, rather than just entertainment.

The Legacy of Political Cinema in Greece

Many today may not be familiar with these directors, but their impact on global cinema is undeniable. Greece, despite being a relatively small country, has long been a cultural powerhouse. While many people focus on its ancient contributions, its modern artistic legacy is just as significant. Greece has produced great poets—Seferis, C.P. Cavafy, Ritsos—and equally remarkable filmmakers.

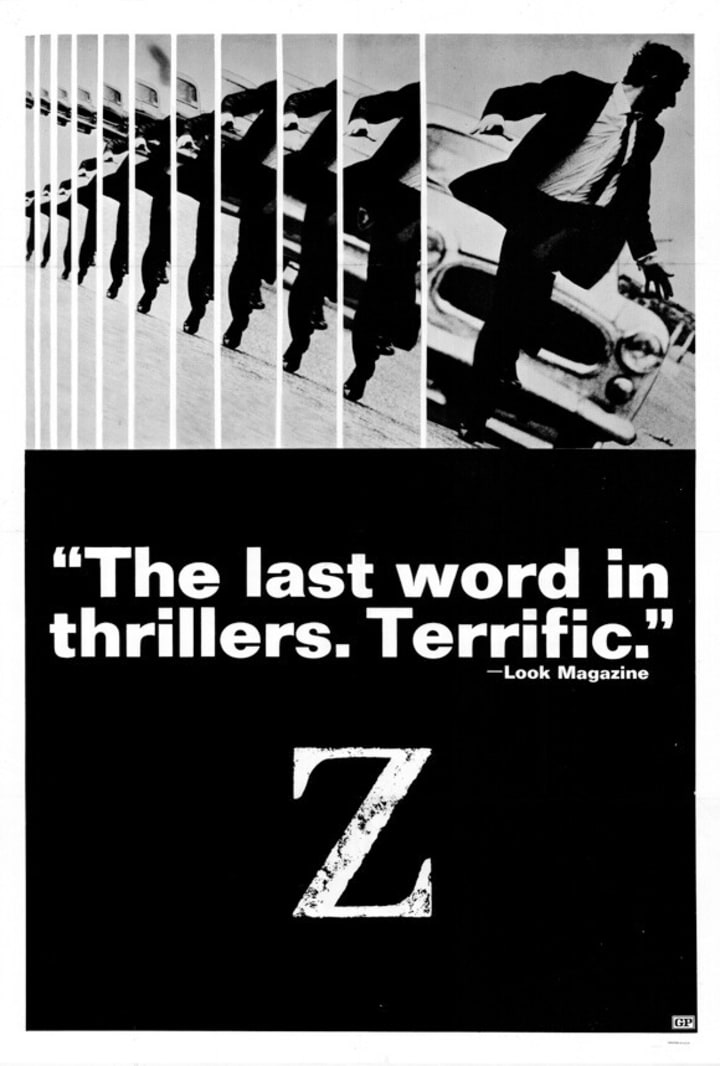

Costa-Gavras is one such filmmaker who left a profound mark on world cinema. His film Missing (1982) tells the harrowing story of an American writer who disappears during the 1973 coup d’état in Chile. The film follows his father and wife as they desperately search for him amidst the political chaos of Pinochet’s rise to power. Another one of his masterpieces, Z (1969), depicts the real-life assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis, a left-wing politician in Cold War-era Greece. Gavras masterfully transforms historical events into gripping cinema, shedding light on political injustices without resorting to propaganda.

This, in my opinion, is what Don't Look Up lacks. I never expected realism in terms of its apocalyptic premise—it is, after all, about a comet heading toward Earth. However, the characters themselves feel like exaggerated caricatures, relying on cinematic clichés. We have the brilliant but misunderstood scientist, the corrupt politicians, the media-obsessed society—all played for satire, but without the nuance that makes political commentary truly impactful. Jonah Hill plays his role effectively, but when nearly every character is reduced to comic relief, the film risks losing its weight. Compare this to The Death of Stalin, which, despite being a satirical comedy, maintains a sense of political realism in its portrayal of power struggles and historical figures.

Theo Angelopoulos: The Poet of Political Cinema

Shifting from Costa-Gavras to another Greek legend, Theo Angelopoulos was a filmmaker who influenced not only cinema but also my own personal worldview. While Gavras inspires political action, Angelopoulos presents cinema as poetry, capturing the sociopolitical landscape of Greece with haunting beauty.

His films often depict lost figures wandering through history. Eternity and a Day (1998) follows a dying poet in Thessaloniki who seeks to complete the work of Dionysios Solomos, the great poet of the Greek Revolution. Ulysses’ Gaze (1995) tells the story of a filmmaker traveling through the war-torn Balkans in search of a lost film reel—perhaps even searching for himself. Though fictional, these films paint an achingly real portrait of political upheaval, displacement, and cultural identity. Angelopoulos was a master of using slow, meditative cinematography to immerse audiences in historical consciousness.

Political Cinema Beyond Greece

Greece is not the only country with a rich tradition of political filmmaking. European cinema has produced numerous films that stand as powerful political statements.

From Germany, The Lives of Others (2006) is a masterful depiction of life in East Germany under Stasi surveillance. The film beautifully captures the oppression of artistic expression under an authoritarian regime, earning it an Oscar, a BAFTA, and multiple Golden Globes. A lighter yet equally political film is Goodbye Lenin! (2003), which humorously explores the transition from East to West Germany through the eyes of a family.

British and Spanish cinema also gave us Land and Freedom (1995), a film that poignantly depicts the Spanish Civil War and the divisions within the left-wing factions fighting against Franco’s regime. Meanwhile, Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini revolutionized political and erotic cinema with films like The Canterbury Tales (1972) and Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), which remain some of the most provocative political films ever made.

Where Are We Now?

Am I being too demanding? Perhaps comparing Don't Look Up to legendary directors is unfair. However, my critique is not just about the film itself, but also about how it was received. Many praised it as a defining political film of our time while overlooking a long-standing tradition of truly groundbreaking political cinema.

Even mainstream films can carry political weight. Trainspotting (1996) by Danny Boyle captures the reality of addiction and societal neglect in Scotland. Sci-fi films like Blade Runner (1982) comment on corporate dystopias and free will, while Star Trek presents an optimistic future where humanity has solved its fundamental societal problems and now grapples with moral and political dilemmas beyond Earth.

More recently, Zola (2021) offered an unfiltered look at exploitation in the sex industry, depicting the social realities of abuse, wealth, and power dynamics in modern America. Though not marketed as a political film, it effectively exposes systemic issues without the need for heavy-handed messaging. In contrast, Don't Look Up spells out its message rather than showing it—breaking one of the fundamental rules of screenwriting: Show, don’t tell.

Political cinema is not dead, but it is becoming less visible. Streaming platforms and corporate monopolization of the film industry make it harder for thought-provoking, independent films to reach mainstream audiences. However, the tradition of political cinema is still alive, waiting for us to rediscover it. Rather than settling for surface-level satire, we should continue seeking out films that challenge, provoke, and inspire meaningful discourse.

Sergios Saropoulos

About the Creator

Sergios Saropoulos

As a Philosopher, Writer, Journalist and Educator. I bring a unique perspective to my writing, exploring how philosophical ideas intersect with cultural and social narratives, deepening our understanding of today's world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.