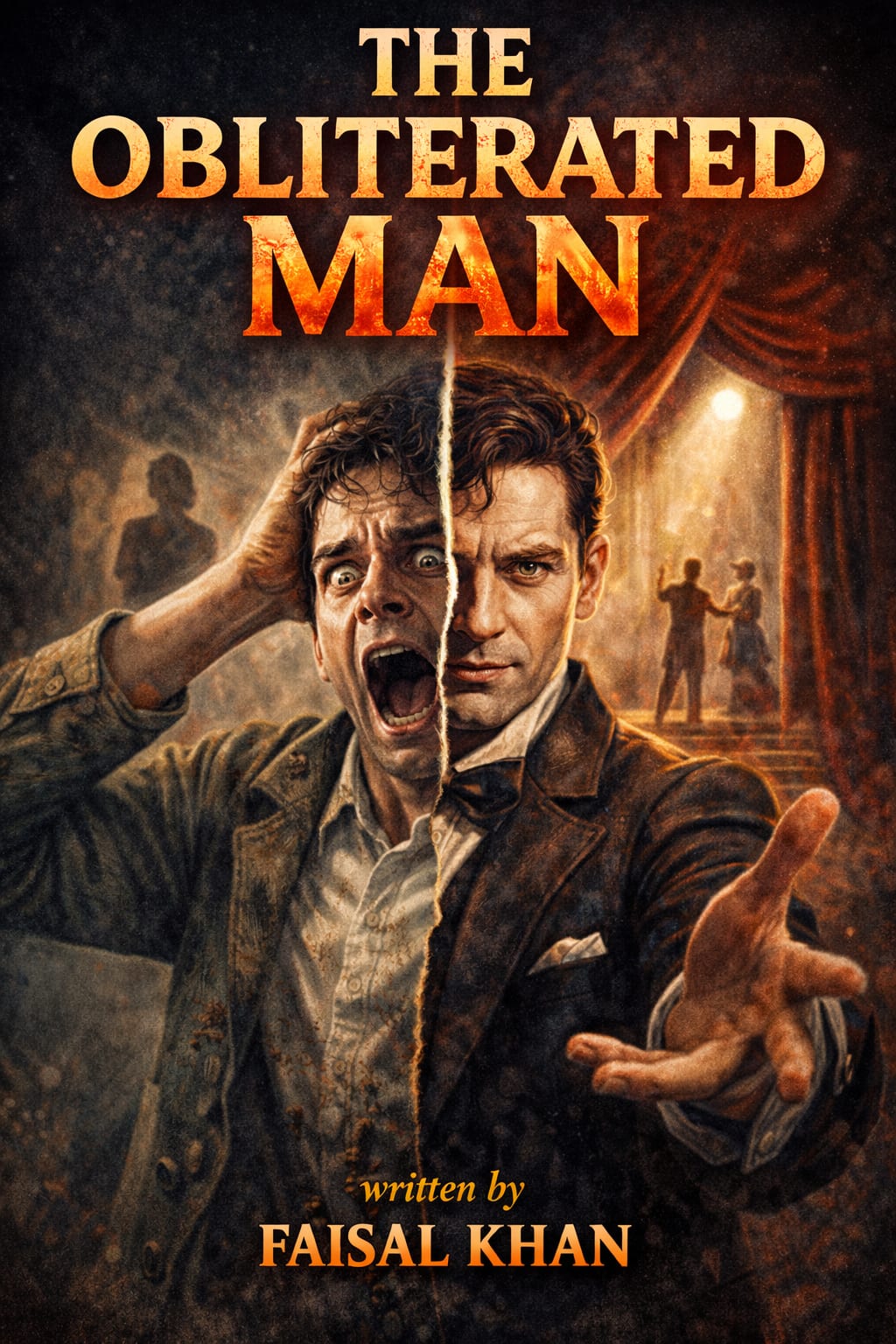

THE OBLITERATED MAN

When a Man Loses Himself to the Stage A Psychological Descent into Performance The Price of Living a Life Not Your Own A Mind Consumed by Imitation From Quiet Man to Living Mask Identity, Art, and the Madness of Pretence The Disease of Becoming Someone Else When Habit Erases the Self

I was—though I am rapidly ceasing to be—Egbert Craddock Cummins. The name remains, but the man does not. I am still, unhappily, the dramatic critic of the Fiery Cross, though what I shall become soon is uncertain. I write this in confusion and distress, for when a man begins to lose his own identity, even telling his story becomes difficult.

Once, I was a quiet, unassuming fellow—shy, slightly stammering, fond of dull grey clothes, and entirely free from dramatic tendencies. I lived a peaceful life and was engaged to Delia, a thoughtful, intelligent girl who valued my sincerity. We shared calm ambitions and modest happiness. I had never been to a theatre; my Aunt Charlotte had warned me against such places, and I had obeyed.

Everything changed when Barnaby, the editor of the Fiery Cross, appointed me dramatic critic. He did so abruptly, catching me in the office one day, thrusting tickets into my hand, and dismissing my objections with cheerful force. I protested that I knew nothing of the theatre and had never attended a performance. Barnaby was delighted by this. My ignorance, he claimed, made me perfect: “Virgin soil,” he called it.

That very night I attended my first play.

The experience overwhelmed me. Accustomed to a quiet, reflective life, I found the exaggerated gestures, unnatural speech, and violent emotions of the actors profoundly disturbing. The audience seemed accustomed to it, but to me it was alarming. The characters claimed to represent ordinary people, yet behaved like creatures possessed. That night I wrote a fierce, indignant review. Barnaby praised it highly.

I slept badly. I dreamed of actors—grimacing, declaiming, clutching their brows and chests. When I awoke the next morning, something was subtly wrong. While dressing, I caught myself making a dramatic gesture entirely foreign to my nature. Later, before the mirror, I found myself imitating stage poses without intending to. At first, I laughed it off.

But the habits spread.

As I attended play after play, the infection deepened. I began bowing extravagantly, striking attitudes in conversation, placing my hand to my brow in moments of stress. I was painfully aware of the absurdity, yet unable to stop myself. My body seemed to act independently of my will. The stage mannerisms clung to me like a second skin.

Gradually, I understood what was happening. My nervous system, always sensitive, was absorbing the theatrical conventions through constant exposure. Night after night, my mind imprinted exaggerated gestures and artificial emotions. The quiet Egbert Cummins—the man Delia loved—was being overlaid by something flamboyant, mechanical, and unreal.

I tried to resign. Barnaby never allowed it. He distracted me with gossip, cigars, and new assignments until my resolve collapsed. Meanwhile, Delia noticed the change.

Our conversations grew strained. She watched me with unease as I bowed, gestured, and spoke with unnatural intensity. I struggled to behave normally, but every attempt only made things worse. The more I resisted, the more exaggerated my actions became.

The crisis came in the British Museum. I approached Delia with theatrical enthusiasm, speaking with emotion I could neither restrain nor justify. She stopped suddenly and looked at me with distress.

“You are not yourself,” she said.

She was right. I tried desperately to return to the man I had been, but my body betrayed me—posing, whispering, gesturing as if before an invisible audience. Delia told me plainly that she disliked what I had become, that my behavior embarrassed her, and that she could not continue our engagement.

When she walked away, I collapsed into dramatic despair, clutching my brow and weeping in full view of the gallery. Even in grief, I could not escape performance. I despised myself for it.

Yet the change did not stop there.

Each day, I grew more theatrical. My clothes became brighter, my hair more stylized, my speech filled with pauses, gestures, and emotional emphasis. I loathed actors, yet found myself drawn to their company because among them my behavior seemed normal. Even Barnaby remarked upon my growing “style.”

I now understand the terrible truth: personality is contagious. For years I had been a quiet sketch of a man. The theatre, with its vivid colors and violent expressions, has painted over me entirely. What remains is not truly myself, but a caricature animated by habit and imitation.

I am being obliterated.

Deep within, I protest, but the protest grows weaker. Each week I attend more plays, reinforcing the infection. My individuality is buried beneath this dramatic casing, pressing closer and closer. I feel like a man encased in armor he cannot remove.

Sometimes I wonder if the only escape is surrender—to abandon ordinary life altogether, adopt a stage name, and step fully onto the boards. Only there, perhaps, will my behavior seem sane. The thought horrifies me. I detest all that acting represents. Yet the world already regards me as absurd.

I try again to resign. Barnaby thwarts me without effort. Letters go unanswered; meetings dissolve into cigars and conversation. The trap tightens.

Soon, I fear, nothing of Egbert Craddock Cummins will remain but the name.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.