The Application That Said No

Rejection became the best direction.

Application rejected. Application rejected. Application rejected.

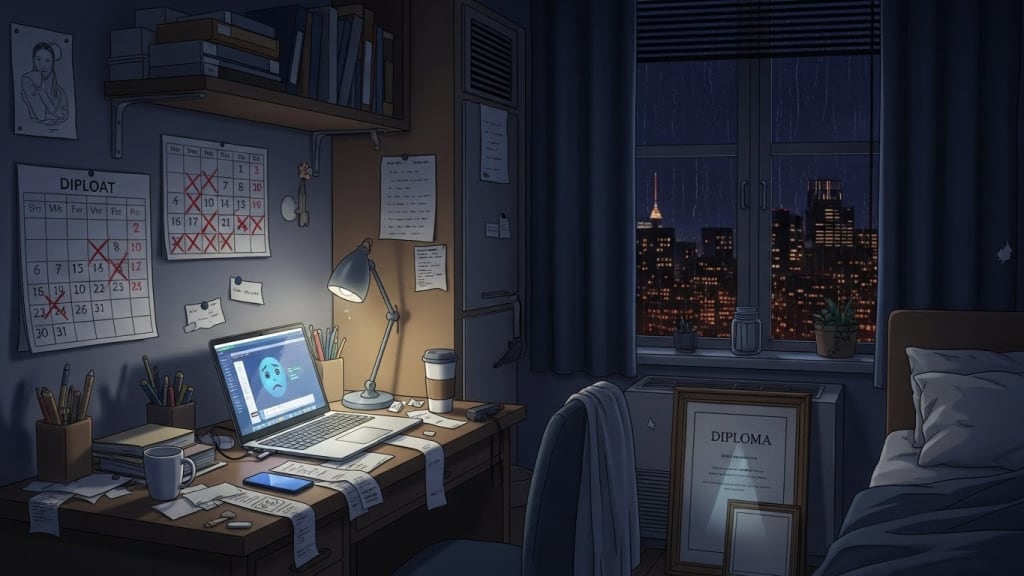

Zara Malik refreshed her email for the hundredth time that day, hoping the words would somehow change. They didn't. Seventy-three job applications in four months. Seventy-three rejections, or worse—silence.

Her master's degree in environmental policy hung on the wall, still in its graduation frame. Two years and sixty thousand dollars in debt for a piece of paper that apparently qualified her for nothing.

The rent was due in six days. Zara had $342 in her checking account.

She closed her laptop and stared at the ceiling of her studio apartment, doing the math she'd done every night for weeks. Even if she got a minimum wage job tomorrow, she'd be evicted before the first paycheck cleared. Her parents had offered help—again—but taking their money felt like admitting defeat. Like proving her father right when he'd said environmental policy was "a passion, not a career."

Her phone buzzed. Another rejection, this time from a nonprofit she'd actually believed in. The email was the standard template: "competitive pool," "impressive qualifications," "moving forward with other candidates."

Translation: you're not good enough.

Zara grabbed her jacket and left the apartment, needing air that didn't smell like failure and instant ramen. The Seattle rain was relentless, soaking through her coat within minutes. She walked without direction, ending up at a coffee shop she couldn't afford.

Inside, a community bulletin board caught her eye. Amid the guitar lessons and roommate searches, one flyer stood out:

"COMMUNITY ORGANIZER NEEDED - Local coalition fighting industrial runoff in Cedar River. Volunteer position. Big impact, no pay. Contact: [email protected]"

Zara almost walked past it. Volunteer work wouldn't pay rent. But something made her photograph the flyer before leaving.

That night, staring at her rejection emails, she drafted a message to Marissa Chen. Not a formal application—she was too exhausted for that. Just honest:

"I have a master's in environmental policy and zero job prospects. I'm probably going to lose my apartment next week. But I care about water quality more than I care about my pride right now. If you need help, I can start immediately."

She hit send before she could overthink it.

Marissa responded within an hour: "Coffee tomorrow? 9 AM. My treat."

The meeting felt different from the dozens of interviews Zara had endured. No panel of stern faces. No questions about her five-year plan. Just Marissa, a sixty-year-old former teacher with fierce eyes and dirt under her fingernails.

"You know this doesn't pay, right?" Marissa said.

"I know. I'm applying anyway."

"Why?"

Zara could have given the polished answer—passion for the environment, commitment to justice, desire to make a difference. Instead, she told the truth.

"Because every job I've applied to wants five years of experience for entry-level positions. They want me to have already done the job I'm trying to get. Nobody will give me a chance to prove myself. So I'm going to prove myself anyway, even if it's for free, because at least then I'll have done something that matters."

Marissa smiled. "You start Monday."

The coalition office was a converted garage behind a community center. Three volunteers, a broken printer, and a filing system that appeared to be organized by chaos. Their mission: stop MegaChem Industries from dumping industrial waste that was poisoning the Cedar River and the neighborhoods downstream.

"We've been fighting this for two years," Marissa explained. "We've got community support, scientific evidence, media attention. What we don't have is someone who understands environmental policy and regulatory systems. That's where you come in."

Zara spent the first week buried in research. MegaChem had exploited a loophole in state regulations, technically complying with outdated standards while devastating local ecosystems. The company had lawyers and lobbyists. The community had passion and Marissa's homemade cookies.

It should have been hopeless.

But Zara found something the lawyers had missed—a provision in the updated Clean Water Act that hadn't been applied at the state level yet. If they could get the state environmental agency to adopt the new standards, MegaChem's permit would be invalid.

She drafted a fifty-page regulatory petition, citing case law and scientific studies, building an airtight argument for updated standards. It took three weeks of eighteen-hour days fueled by free coffee and the strange satisfaction of work that actually meant something.

Meanwhile, her bank account hit zero. She sold her furniture. Moved into Marissa's spare room "temporarily." Picked up gig work delivering food between coalition meetings.

Her parents called weekly, offering money, begging her to "be realistic."

"This isn't sustainable," her father said. "You can't eat principles, Zara."

"I know. But I can't live without them either."

The state environmental agency accepted their petition for review—a small miracle. Then the real work began. Public hearings, testimony, mobilizing community members to show up and share their stories. Zara learned that policy wasn't just about regulations—it was about people.

She met families whose kids had chronic respiratory issues. Fishermen who'd watched their livelihoods disappear. Elders who remembered when the river ran clear. Their stories became her fuel when exhaustion threatened to break her.

Four months into the volunteer position, something unexpected happened. A reporter from the Seattle Times wrote a feature about the coalition's fight. She interviewed Zara, who explained the regulatory strategy in terms regular people could understand.

The article went viral locally.

Two days later, Zara got an email—not a rejection, an offer. The state environmental justice office wanted to hire a policy analyst. They'd specifically requested her.

"We've been following your work with Cedar Voices Coalition," the hiring manager said during the interview. "You have something rare—technical expertise combined with real community organizing experience. Most candidates have one or the other. You built both simultaneously."

The salary was modest but survivable. The work was meaningful. The irony wasn't lost on Zara—she'd gotten the job by doing the work for free that nobody would hire her to do.

On her last day volunteering, the coalition held a small celebration. The state had adopted the updated water quality standards. MegaChem's permit was under review. They hadn't won yet, but they'd shifted the battlefield.

Marissa hugged her fiercely. "You saved us, you know."

"You saved me first," Zara replied. "You gave me a chance when nobody else would."

"No. We gave each other a chance. That's how this works."

Zara started her new job the following Monday. Her first assignment was reviewing another community petition about industrial pollution—the same situation she'd just lived through, but from the other side of the regulatory system.

She thought about all those rejection emails. Seventy-three times she'd been told she wasn't qualified, wasn't experienced, wasn't ready.

They'd been right and wrong simultaneously.

She wasn't ready for those jobs because those jobs would have made her small—filing reports, attending meetings, maintaining systems that didn't challenge the status quo.

The rejection had pushed her toward work that made her larger—capable, creative, connected to something beyond a paycheck.

Sometimes the doors that close aren't keeping you out. They're protecting you from rooms too small for who you're becoming.

Six months later, Zara was invited to speak at her graduate program about career paths in environmental policy.

Standing before anxious students clutching resumes and wondering if their degrees were worthless, Zara told them the truth:

"You're going to get rejected. Probably a lot. And each rejection will feel like confirmation that you made a mistake, that you're not good enough, that you should have chosen something practical.

But here's what I learned: rejection isn't the end of your story. It's a redirection. The question isn't whether you'll face closed doors—you will. The question is whether you'll let those closed doors define you, or whether you'll find the work that matters and do it anyway, even when nobody's paying you, even when nobody's watching, even when everyone thinks you're being unrealistic.

Because the world doesn't need more people who took the safe job they didn't care about. It needs people who got rejected seventy-three times and showed up for the seventy-fourth fight anyway."

The students looked skeptical. Zara didn't blame them. She'd been skeptical too.

But six hands went up after her talk, asking about volunteer opportunities in environmental justice work.

And Zara smiled, remembering that rainy night when she'd photographed a flyer for a position that didn't pay anything except purpose.

Sometimes the best application is the one that says no to everything that doesn't matter so you can say yes to everything that does.

Even if it takes seventy-three rejections to find it.

About the Creator

The 9x Fawdi

Dark Science Of Society — welcome to The 9x Fawdi’s world.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.