Pretty Girls Cosplay Disability

Overcoming self-induced physical limitations for femininity

"One of my biggest fears is fainting, 'cause I feel like the dresses, they get heavier and heavier. (...) and I might pass out." Cardi B, Met Gala 2024

Introduction

For a long time, gender expression for women, whether that be through esthetic procedures, beauty maintenance or fashion, has been a synonym for discomfort. From the corsets of the romantic era, to the 21st century Met Gala’s extravagant requirements, the standards of beauty for women have been plenty, and the requirements to be feminine, strongly linked to being beautiful. Such standards of performance thus leave out women who struggle to hit all or most of them, notably disabled women. This article looks at the link between the physical limitations and discomfort induced by aesthetic decisions women make to attain emphasized/dominant femininity and, the perhaps, at first glance contradictory exclusion of physically disabled women who live with these limitations from our collective understanding of femininity. In other words, how is the feminine essence we perceive as exuding from able-bodied women who limit their own abilities a conversation about overcoming discomfort, complimentary nature and domination, conversation that should be seen through a gendered disability lens. To illustrate this argument, I will highlight the extreme performances of femininity showcased at the Met Gala and studies done on regular women’s relationship with feminine fashion and lingerie, using Connell’s (1987) framework of masculinities and Messerschmidt (2011) and Schippers’ (2007) frameworks of femininities as those last two understand femininities as existing within their own hierarchy.

Literature review

Femininity and discomfort

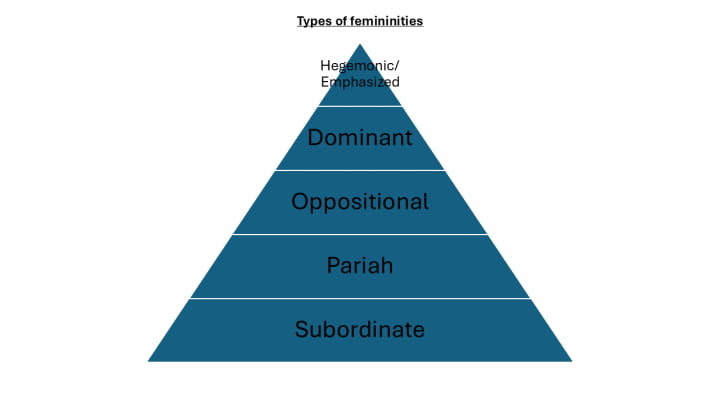

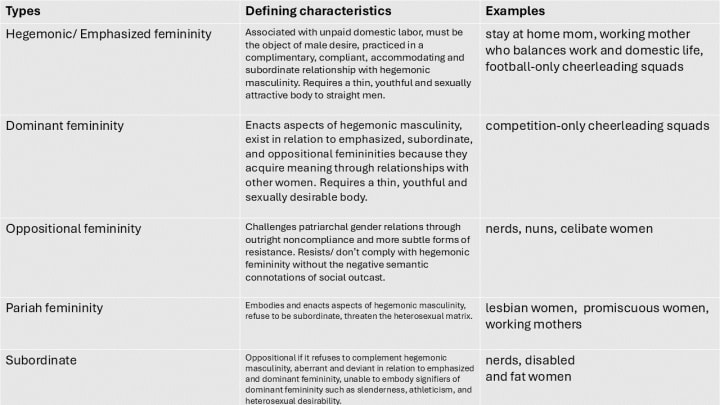

Charlebois (2010) quotes Connell’s (1987) concept of emphasized femininity and not hegemonic femininity as calling it that would not adequately capture the power dynamics between the genders, that is, the domination of men over women. The existence of hegemonic masculinity when embodied by some men is the reason as to why we legitimize the patriarchy and the overall subordination of women to men (Schippers, 2007). According to Connell (1987), femininity can never be hegemonic because it exists in constant subordination to masculinity. Thus, emphasized femininity is “practiced in a complimentary, compliant, and accommodating subordinate relationship with hegemonic masculinity” (Charlebois, 2010, p.26). Both hegemonic masculinity and emphasized femininity exist in a hierarchical relationship with other gender performances, the latter especially in relation with non-empahsized and therefore subordinate femininities (Charlebois, 2010). While hegemonic masculinity desires the feminine object, emphasized femininity must be the object of male desire and exists to be the subordinate of hegemonic masculinity (Charlebois, 2010). Schippers (2007) views femininities as existing in a hierarchy of their own in a state of subordination to hegemonic masculinity. Dominant femininities are described as “the most powerful and/or the most widespread type in the sense of being the most celebrated, common, or current form of femininity in a particular social setting” (Charlebois, 2010, p.27), Charlebois giving the example of competition-only high school cheerleaders saying that they embody a sought after feminine ideal but they are not emphasized as they do not exist to support the expansion of hegemonic masculinity, and in the case where some of these female athletes take their career and athleticism very seriously, they are challenging the mainstream belief that high level sports are not a field made for women.

Emphasized femininities require the manipulation of female bodies as it relies on the idea that these bodies require fixing (Charlebois, 2010). Thus, emphasized femininity is unattainable for many, especially due to its geographically and historically mobile nature and the discomfort it often requires (Charlebois, 2010). Though for a while such discomfort was more normalized, the need for women to wear more comfortable clothes was precipitated by their entry in social life. The comfort and practicality of jeans and flatter shoes versus skirts and corsets seems obvious when one has to take on a larger scope of activities, work and tasks. However, when one is not expected to perform such work, or perhaps that their only task is to perform beauty and be gazed at, such practicality and comfort seems to be less of a necessity. The standards of beauty expected of women, especially in the context of high fashion, red carpets or emphasized idealized femininity seem to long for a reverting to older aesthetics that are physically limiting. Pursuing beauty and sexiness is a race that “requires considerable time, money, effort, pain, and self-discipline”, and moreover, the ideal standing at the finish line is extremely difficult to attain, if not plainly unattainable for most (Chrisler, 2012, p.118).

Historically, disabling practices have been used by women in order to increase their femininity, beauty and value, examples including foot-binding, high heels, corseting, and heavy jewelry, some including disordered eating and diets, and their impacts for the higher purpose of looking thinner and therefore more feminine (Scott, 2015; Chrisler, 2012; Charlebois, 2010). Temporary pain or loss of mobility as the aftermath of invasive plastic surgery (e.g., breast augmentation, Brazilian butt lift), or less invasive procedures (e.g., botox injection and fillers) (Chrisler, 2012; Charlebois, 2010) can also be included in the enumeration of disabling practices women take on in order to appear more feminine. The normalization of such practices ultimately teaches women and girls that their appearance is more important than their capabilities (Charlebois, 2010).

Sayings such as “pretty hurts” or “beauty is pain” which are almost exclusively directed at women are a good example of the normalization of pain as a requirement for idealized femininity. When such pain cannot be overcome by women who do not have such ability, beauty perception is lowered and femininity unachieved. However, I would argue that the limitations inflicted on women are not all that makes them feminine but rather their ability or partial ability to overcome them with what we perceive to be grace, or at least, silence, all this with maintaining homogeneity in the feminine landscape. An interview-based project looking at British women’s relationship with lingerie highlighted the necessity to hide the physical and emotional labor required before a successful sexual spectacle (Woods, 2016). In this piece, Woods (2016) quotes Ferreday saying: “the feminine subject must constantly work to conceal the labour and anxiety involved in its production” (p.18), and to be feminine is to be “beautiful, or doing everything possible to try to be beautiful” (Chrisler, 2012, p.119).

Lingerie is a good and more accessible example of the discomfort women inflict on themselves for the larger goal of femininity and sensuality, whether that be for themselves or for the gaze of an often-male partner. Participants in Wood’s study (2016) expressed feeling like “the sexier the underwear the less comfortable it tends to be” (p.12), almost as though the bending, pushing and tightness of those cuts are what makes them alluring; the discomfort they cause always silenced. Said resistance to this discomfort is even more so imperative considering the constant scrutiny femininity lives under. Postfeminist visions of sexuality locate femininity as a part of the feminine sexually appealing body and said feminine sexy body as “requiring constant surveillance and improvement” (Wood, 2016, p.13). Some view womanhood as being ascribed, meaning that if one is female, one is a woman, as opposed to manhood which is believed by some as being earned through hard work (Chrisler, 2012). However, such position can only be maintained if one doesn’t perceive femininity as a requirement to be a “real” woman and if this constant “body work” isn’t considered work.

Disability, sexuality and femininity

Disability as an identity is deeply gendered (Mohamed & Shefer, 2015), specifically through the way that it is routinely degendered, or sometimes even seen as a third gender (Hunt, 2021). Ideas about sexuality have traditionally been extremely sexist and ableist, putting disabled women in a marginalized position when talking about their perceptions as sexual and gendered beings (Campbell, 2019). The narrow range of appearances we deem acceptable when it comes to women and beauty standards results in an almost systematic exclusion of disabled women when it comes to our framings of beauty but also of being a woman (Zitzelsberger, 2005; Campbell, 2019). Physically disabled women are then hyper visible and invisible depending on the context. Invisible because they are assumed to not partake in sexual life as a way to alleviate the discomfort able-bodied people feel regarding the mixing of sex and disability (Overstreet, 2008; Parritt and O'Callaghan, 2000), and hyper visible because they are visibly different (Zitzelsberger, 2005). To this is added the questioning of their reproductive, motherly and romantic abilities which affects our understanding of their gender performances, these abilities being so intimately tied with femininity and womanhood (Zitzelsberger, 2005; Hunt, 2021, Chrisler, 2012). They have historically been infantilized and characterized as unattractive which also participates in their asexualization, (Mohamed & Shefer, 2015; Hunt, 2021), and the lived sexual experiences of physically disabled women remain largely understudied (Campbell, 2019) which encourages the perpetuation of this myth, that is, that this demographic is asexual by virtue of being disabled and female. The lived experiences of women with disabilities and others’ perceptions of their gender can be seen as a contradiction (Cheng, 2009). Attributes such as “fragile, delicate, helpless, and docile” can be associated with hyperfemininity and disabled women, however, such terms can also be associated with lack of independence, agility, grace and strength which then hinder their “ability to perform cultural roles deemed traditionally feminine” (Scott, 2015, p.230; 233; Cheng, 2009). The discomfort or limitations induced by able-bodied women in order to perform femininity when embodied by physically disabled women are not seen as feminine, but rather as agendered, as it is supported that “disability negates femininity rather than boys it” (Hunt, 2021, p. 68). Moreover, Chrisler (2012) asserts that women are offered two paths, two options of performances in order to demonstrate their womanhood, “the pursuit of beauty” and the path of the “good” mother (p.118), which explains why disabled women who struggle using the first path, and who are assumed to be infertile or incapable of being a “good” mother then become genderless. This degendering of disability also explains why men with disabilities experience being degendered as well; disability being attached with characteristics such as being helpless and dependent whereas masculinity is seen as requiring powerfulness and autonomy, thus disqualifying them (Shuttleworth, Wedgwood & Wilson, 2012). In other words, disability acts as a disturber for femininity and disabled women experience sexism without its perceived benefits (Mohamed & Shefer, 2015).

Using Connell’s framework, visibly physically disabled women and girls then occupy a subordinate form a femininity as it “refers to those femininities situationally constructed as aberrant and deviant in relation to both emphasized and dominant femininities” (Messerschmidt, 2011, p.206) as they might be unable to take on some of the characteristics required for emphasized/dominant femininities such as thinness, athleticism and heterosexual desirability. Another example of subordinate or perhaps more oppositional femininity would be that of women nerds who reject some dominant characteristics by choice and prioritize their intellect in ways we don’t encourage girls to do, their femininity being subordinate and oppositional (Charlebois, 2010). The label of oppositional can be applied to femininities that, in “their embodied practice—either intentionally or unintentionally—refuses to complement hegemonic masculinity in a relation of subordination” (Messerschmidt, 2011, p.206). In the case of physical disability, this might be intentional in the case of women who could technically endure the elevated pain of standing in painful heels, or unintentional in the case of women with scoliosis for who a corset would never give them an hourglass figure.

The MET Gala

Every first Monday of May, the Met Gala wakes up the fashion critique in many. This fundraiser for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute is popularly known as a night for high fashion and eccentric gowns (as it is organized by Vogue Magazine), the women being the guests that get most of the attention. The red carpet of the event takes place in the stairs of the museum, guests being expected to go up the stairs until ready to get inside for the event. This event is a display of gender performances coming from some of the world’s most idealized celebrities, writing gender scripts so unattainable some perhaps see them as idealized. Vogue Magazine’s Youtube channel has been for a few years documenting the process of Met Gala attendees getting ready for one of fashion’s biggest night, narratives that garner every year millions of views. These narratives, in some cases, feature women’s painful struggles towards their envisioned look, struggles sometimes noticeable on the red carpet during the event.

The historical feminization of physically limiting (or sometimes harmful) clothing, diets, beauty regiments and procedures existing simultaneously next to the exclusion of disabled women and disability as a whole in gender conversations has led to an intensification and perceived lack of femininity for this demographic (Scott, 2015). This is seen every year at the Met Gala as women report and are shown wearing dresses so uncomfortable they can’t breathe, or sit in them, (Vogue, 2019), are seen needing to be escorted up the stairs by security as they cannot walk independently in their choice of clothes (Vogue, 2024a), or even being pricked by needles as the dress is sewed onto them (Bonner, 2024; Chiorando, 2024 ). Other guests have also mentioned being scared of fainting due to the heat combined with the weight of their dresses (Vogue, 2024b), or being open to wearing adult diapers as a way to avoid the bathroom (Chiorando, 2024). All of those experiences are reminiscent of disabled experiences, as they emulate symptoms of various health conditions including reduced mobility or chronic pain in the case of difficulties walking and sitting, limited lung function in the case of difficulties breathing, heart problems in the case of fainting, and poor bladder/bowel control in the case of diaper use. However, in the case of female Met Gala attendees, these symptoms are induced for the very purpose of aesthetics and femininity in the context of high fashion. Thus, to showcase such pain and such grace, a cosplay of disability is undertaken by these women through fashion and other aesthetic choices that puts physical limitations on their bodies to then prove they are able to overcome them, whether that be through simply pushing through, having to be carried up the stairs or have an assistant holding the back of a dress.

The Met Gala is mostly famous for its red carpet which takes place in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute’s front stairs. For this reason, wheelchair users would be forced to enter the venue through the accessible back entrance, missing the glamour of the carpet. Every year, the absence of visibly disabled guests is observed, maintaining the status quo. In 2024, a few outlets pointed out the lack of accessibility of the event and therefore lack of visible disability representation on the carpet, with seemingly no responses from the organizers. The continued invisibility of disabled people leads to their exclusion, and ultimately to the belief that accessibility is not a necessity, especially not in spaces of leisure or that promotes desirability and “polished” appearances, as able-bodied people often assume that “people with physical disabilities do not and should not care about their appearance’’ (Zitzelsberger, 2005, p.395). This exclusion and invisibility of disability is even more so paradoxical as the red carpet is every year presenting women who, in order to be noticed and be the most visible, cosplay disability. Furthermore, an argument could be made that it is this very pushing of the limits of the female body that makes the Met Gala an enticing night for fashion, the glamorization of discomfort for the purpose of femininity.

Watchers of the YouTube videos narrating the creation of these high fashion looks enjoy taking a look into the long process of dress fitting, make up and hair taken on by those female guests, perhaps the closest thing these regular women will get to observing the building/reproduction of those unobtainable beauty standards they might have fallen at the mercy of. As they hear famous actresses and models describe the pain they are under as they aim to replicate a silhouette clearly contradictory to their body shape, the listeners are likely to forget the “before” appearance and focus on their own incapability to replicate the “after” look present on the red carpet, while overall taking pleasure out of this spectacle.

These female bodies ‘become’ and then create femininity through a series of negotiations: constraint, anxiety, alienation, playfulness, pleasure and empowerment (Frost, 2005); the physical constraints caused by the corset, the anxiety of falling due to the high uncomfortable heels and the alienation caused by knowing the pain that went behind this performance which was in the end unnatural. However, as mentioned prior, this performance of femininity can still be pleasurable for the performers and the attendance, the latter being able to mimic such preparation, surprise and presentation in their own lives when buying and putting on lingerie for a partner for example as mentioned by Wood (2016). With that said, feminist scholars have argued that this work is taken on, even if it is oppressive because women know that the abandonment of this performance would lead to a severe loss of status, respect, lovers and job opportunities, and lead to harassment and mockery (Chrisler, 2012). Perhaps, part of the enjoyment of this work is a form of coping mechanism in face of the reality that this race and their semi-success in it might afford them temporary safety from another kind of storm.

Homogeneity and femininity

The other factor to consider in this conversation is the one of homogeneity, meaning of non-disruption of the established environment and social norms. When the overcoming of physical limitations in order to attain femininity is being done through means we perceive as disrupting the status quo or overall aesthetic of a space, such overcoming is no longer celebrated and is perceived as a failure, an example being mobility aids like wheelchair, canes or alternative architecture such as ramps. The Foucauldian theory of the ‘docile body’ echoes this on a larger scale, framework used by Bordo (1993) in her own work to describe the role of the body in the process of accommodation and resistance to power. Through their consumption of homogenous cultural images of femininity, women internalize this homogeneity and learn to modify themselves in order to fit in, this sometimes daily ritual becoming normalized, perhaps as being a form of self-discipline, that is sometimes pleasurable (Bordo, 1993). Beauty regiments and carefully curated wardrobes then become requirements for the passing of the surveillance test one has to take in order to appear feminine.

Feminine aesthetics are constantly changing, whether that be through the seasonal shifts of female fashion, magazines and high fashion designers acting as a compass, or through the popularizing of certain makeup techniques and haircuts. Idealized femininity is unattainable because it is always changing yet somehow homogenous, and it is that homogeneity that leaves visibly disabled women out of its frame. So much of disability/accessibility tools exist as ways to accommodate and resist inaccessibility, however, such tools often break this homogeneity, which leads to the perception of a failed reproduction of femininity in this ideal form. Perhaps, the failure of the physically disabled female body to attain ideal femininity doesn’t come from its assumed limitations (meaning inability to produce children, climb stairs, breathe unassisted, etc) and the consequent moral judgments attributed to them, but from its unruliness and perceived resistance to the winds of constant external regulation.

Disabled women’s refusal or inability to partake in uncomfortable beauty rituals and fashion is a transgression of the expectation of docility we require of women and femininity. And for the disabled women who do it with assistance (for example wearing high heels while sitting in a wheelchair), their disruption of the homogenous landscape leads to the complete or partial rejection of their performance.

With that said, it must be reemphasized that emphasized femininities exist as subordinate to hegemonic masculinity (Charlebois, 2010), subordination even more so palpable when we are reminded of the often-required limited abilities of the women aiming to perform this femininity. Furthermore, “hegemony is maintained through constructing complementary but asymmetrical relational differences between men and women”, this complementary asymmetry present in the requirement that men be physically strong and the continuous physical weakening of women through extreme dieting, tight clothing and painful footwear (Charlebois, 2010, p.29). And so perhaps, one could argue that through our encouragement of women to disable themselves for the higher purpose of beauty, these performances get closer to emphasized/hegemonic femininity and its complimentary nature. Moreover, “Schippers’s point that the relationship between masculinity and femininity extends beyond difference and instead revolves around an axis of dominance and submission” (Charlebois, 2010, p.30), meaning it is not just women weakening their abilities to be complimentary to the strength we attribute to men but rather the process of able-bodied women being submissive to the male gaze and putting their body in a state of sometimes extreme domination for a night. Characteristics of hegemonic/emphasized femininity ultimately further disempowering them, giving these women privilege that is paradoxical (Charlebois, 2010).

The femininities displayed at the Met Gala are as diverse as the female guests attending. Though many guests are high profile celebrities, thin bodies represent the majority of attendees. Plus size model Ashley Graham sharing a few years ago that though she was invited to the Met in 2016, she did not go because could not find a designer to dress her (Russo, 2018), and as mentioned prior, visibly disabled women are absent. I would argue that the women at the Met Gala display femininities usually ranging from oppositional to hegemonic, and those displays exist in the frame of their everyday display of femininity, meaning, it is usually a continuation or a slight expansion of the performance they take on in their everyday public live as actresses, models, singers and influencers. Women who are labelled as having more oppositional forms of femininities are likely to still be viewed as such at the Met Gala, examples such as publicly queer actress and producer Lena Waithe, known for her more masculine/androgynous fashion sense. As mentioned, a good number of the female guests are working women, who work in entertainment. As mentioned by Charlebois (2010), hegemonic ideals for women are location and time dependent meaning in certain contexts, hegemonic femininity will be a stay-at-home mom while in others, it will be the working mom who at night takes on the domestic work. In the Hollywoodian context and when talking about high profile female celebrities, this differs because it’s assumed that they pay lower class women to perform those domestic tasks, meaning they do not take on the feminine tasks we expect women to do in the home, while others do not have children at all and/or are single. Dominant and hegemonic femininities are displayed at the Met Gala through their appeal to the male gaze, their high preoccupation for beauty and especially through displaying a more traditional ideal of beauty including thinness and uncomfortable garments. Not all these performances are hegemonic/emphasized because they don’t always exist as means to uphold hegemonic masculinity, but they are still, for the most part, dominant as they are overpowering subordinate and oppositional femininities. Another vision comes from Schippers (2007) who argues that in the case of racialized femininities, those are not necessarily subordinate as they can empower non-white women who do not desire to embody white feminine ideals.

In the case of disability, pariah femininities which is described as “the quality content of hegemonic masculinity enacted by women” doesn’t fully apply because disabled women who cannot wear high heels and tight clothing might be refusing the idealized feminine performance, but they are not taking on the characteristics of masculinity (Schippers, 2007, p.95). Examples of a pariah femininities being “the slut” or “the bitch”, who are women who are sexually liberated or authoritarian, characteristics that we have made acceptable for men but that we stigmatize in women (Schippers, 2007). Physically disabled women at the Met Gala would likely represent a subordinate type of femininity as they would be unable to perform able-bodiedness, be unable or strongly struggle to go up the stairs, etc, this subordination coming from their body display (Messerschmidt, 2011).

This homogeneity is also maintained through the trivialization or full-on refusal to address the labour that goes behind these painful attempts at achieving the feminine ideal. In opposition, the presentation of boys’ journey towards manhood being a large part of our media and culture (e.g., action movies or “bro” culture) leads to a common belief that boys have to work so much more to become men than girls do to become women; because the journey girls take must be taken in silence. Judith Butler’s work on gender reminds us of the perpetual incompletion of the gender performance as one is never fully feminine or masculine enough (Scott, 2015), and yet, most women remain blind or purposefully mute to this discomfort in order to not break the vision of these feminine ideals which are unattainable. Men remaining unaware of this beauty work reinforces patriarchal ideas about men being the active and work focused gender, and pressuring women to maintain this ignorance by not speaking about this work keeps them controlled, under the foot of the patriarchy (Chrisler, 2012). To be mute about the journey towards unattainable beauty ideals reinforces its hegemonic and homogenous nature as it supports the idea that femininity is both made yet natural.

Conclusion

As mentioned throughout this piece, the pressures women live under in order to fit the narrow box of desirability have been normalized and internalized by them, sometimes turning this labor and pain into a pleasurable and empowering process. The Met Gala in the 2020s exists as a display of the process of creation and reproduction of beauty standards and gender ideals, process that many wait for every Spring, though rarely questioning the link it has with disability. Feminine ideals of beauty are linked with disability since femininity has for centuries required the limitation of women’s comfort and sometimes health to achieve thinness, a specific silhouette or the display of garments. Physical limitations are not inherently unfeminine or unattractive, as those are cosplayed by able-bodied women all the time for the very purpose of showcasing femininity. This contradiction, that is, both the applaud of physical limitations when self-inflicted and the disdain of them when permanent, is perhaps inherently feminine because femininity as we perceive it requires contradiction: the silent construction of a feminine spectacle that should be painfully pleasurable.

References

Bonner, M., 2024, 07 May. "Dove Cameron is a floral dream at the 2024 Met Gala in a dress with trailing sleeves". Cosmopolitain, . https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/fashion/celebrity/a60714433/dove-cameron-2024-met-gala-dress/

Bordo, S. (1993). Unbearable weight : feminism, Western culture, and the body. University of California Press.

Campbell, M. (2019). “Nobody Is Asking What I Can Do!”: An Exploration of Disability and Sexuality. (Doctoral thesis, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada). Retrieved from https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/985832/

Charlebois, J. (2011). Gender and the construction of hegemonic and oppositional femininities. Lexington Books. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10444494

Cheng, R. P. M. (2009). Sociological Theories of Disability, Gender, and Sexuality: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 19(1), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911350802631651

Chiorando, M., (2024, May 7). How DO stars get into their outrageous Met Gala gowns? From being sewn into dresses to wearing adult nappies to avoid toilet trips, it's not all glamour behind the scenes! DailyMail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-13391595/How-stars-outrageous-Met-Gala-gowns-sewn-dresses-wearing-adult-nappies-avoid-toilet-trips-not-glamour-scenes.html

Chrisler J.C. (2013). Womanhood is not as easy as it seems: Femininity requires both achievement and restraint. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 14(2), 117–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031005

Connell, R. W. (1987). Gender and power : society, the person and sexual politics. Polity in association with Blackwell.

Frost, L. (2005). Theorizing the Young Woman in the Body. Body & Society, 11(1), 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X05049851

Hunt, X., Braathen, S.H., Rohleder, P. (2021). Physical Disability and Femininity: An Intersection of Identities. In Hunt, X., Braathen, S.H., Chiwaula, M., Carew, M.T., Rohleder, P., Swartz, L. (eds) Physical Disability and Sexuality. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55567-2_4

Messerschmidt, J. W. (2011). The Struggle for Heterofeminine Recognition: Bullying, Embodiment, and Reactive Sexual Offending by Adolescent Girls. Feminist Criminology, 6(3), 203–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085111408062

Mohamed, K., & Shefer, T. (2015). Gendering disability and disabling gender: Critical reflections on intersections of gender and disability. Agenda, 29(2), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2015.1055878

Overstreet, L. C. (2008) Splitting Sexuality and Disability: A Content Analysis and Case Study of Internet Pornography featuring a Female Wheelchair User. (Master’s thesis, Georgia State University, USA). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_theses/22/

Parritt, S., & O'Callaghan, J. (2000). Splitting the difference: an exploratory study of therapists' work with sexuality, relationships and disability. Sexual & Relationship Therapy, 15(2), 151–151.

Russo, Gianluca. (2018, May 8). People think the Met Gala made a glaring mistake on the red carpet — and it points to a larger problem in fashion. Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/met-gala-models-diverse-body-types-2018-5

Schippers, M. (2007). Recovering the Feminine Other: Masculinity, Femininity, and Gender Hegemony. Theory and Society, 36(1), 85–102.

Scott J.-A. (2015). Almost Passing: A Performance Analysis of Personal Narratives of Physically Disabled Femininity. Women’s Studies in Communication, 38(2), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2015.1027023

Shuttleworth R., Wedgwood N., & Wilson N.J. (2012). The Dilemma of Disabled Masculinity. Men and Masculinities, 15(2), 174–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X12439879

Vogue. (2019, May 7). Kim Kardashian West Gets Fitted for Her Waist-Snatching Met Gala Look | Vogue [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bk0G1f4DpCM&t=98s&pp=ygUca2ltIGthcmRhc2hpYW4gbWV0IGdhbGEgMjAxOQ%3D%3D

Vogue. (2024a, May 6). Tyla wears Balmain at Met Gala 2024 [Video]. Youtube. https://youtube.com/shorts/91vSfp_K5Fk?si=RW_pRWuWWip-QBD4

Vogue. (2024b, May 8) Cardi B Gets Ready for the 2024 Met Gala | Last Looks | Vogue [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TNZYr7RwcoM&t=19s&pp=ygUVY2FyZGkgYiBtZXQgZ2FsYSAyMDI0

Wood, R. (2016). ‘You do act differently when you’re in it’: lingerie and femininity. Journal of Gender Studies, 25(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2013.874942

Zitzelsberger, H. (2005). (In)visibility: Accounts of embodiment of women with physical disabilities and differences. Disability & Society, 20(4), 389‑403. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590500086492

About the Creator

Allie Pauld

Sociology and sexuality graduate trying to change the world. Nothing more, Nothing less.

Montreal based disabled, LG[B]TQ+, Pro-Black Feminist.

You can find me at @allie.pauld on Instagram.

Comments (1)

oh